Today’s blog post will take us to South Eastern Europe, namely to Greece, and to some vocabulary around the theme of shopping.

Tag Archives: learning languages

Hebrew vocabulary: Rosh Hashana

This week’s blog post is taking us to Israel and to the Jewish diaspora again and we are going to look at the vocabulary related to the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashana ראש השנה, which was celebrated this week, and the foods that are usually eaten on this holiday (these vary depending on the country of origin).

The vocabulary of ‘Harry Potter’ in Romanian, Czech, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish

Romanian

Hogwarts is called Hogwarts Școala de Magie, Farmece și Vrăjitorii in Romanian. Voldemort is Cap-de-Mort, and Harry is the Boy Who Lived or „băiatul care a supraviețuit”. Muggles are Încuiați, non-magical people of wizard descent or Squibs are noni, half-blood wizards are „sânge-semipur” and Mudbloods are „sânge-mâl”. The 4 houses are Cercetași (Gryffindor, lit. ‘scouts’), Astropufi (Hufflepuff), Ochi-de-Șoim (Ravenclaw, lit. ‘Falcon Eye’) and Viperini (Slytherin, lit. ‘pertaining to vipers’). The Death Eaters are Devoratori ai Morți and Mad-Eye Moody is called Ochi-Nebun Moody. Quidditch is Vâjthaț, the Sorting Hat is called Jobenul Magic care face Sortarea and The Burrow is Vizuina and Diagon Alley is Aleea Diagon. The London wizarding pub The Leaky Cauldron is La Ceaunul Spart and the street Knockturn Alley becomes Nocturnalee (‘Nocturnal Alley’) in the Romanian version.

Czech

In the Czech edition of Harry Potter, Hogwarts is called Škola čar a kouzel v Bradavicích (from bradavice meaning ‘wart’) and the village of Hogsmeade is Prasinky (from prase = pig, swine, hog). Diagon Alley is Příčná ulice, lit. the ‘straight street’, and Knockturn Alley is Obrtlá ulice. The Weasleys’ home The Burrow is Doupě and The Leaky Cauldron is Děravý kotel. The four houses of Hogwarts are Nebelvír (from nebe = ‘sky‘ and lvír -> lev = ‘lion’) for Gryffindor, Hufflepuff is Mrzimor, Ravenclaw is Havraspár (from havran = raven, and spár = claw) and Slytherin is Zmijozel ( zmijozel = ‘adder’, and zmije = snake, viper, and zlo = evil).

Norwegian

The Norwegian edition is interesting from a language aspect, since nearly all names and terms have been changed to a more Norwegian version. Hogwarts is called Galtvort høyere skole for hekseri og trolldom and the village of Hogsmeade is Galtvang (both from ‘galt‘ meaning ‘hog’). Dumbledore is called Humlesnurr, Professor Snape is Professor Slur, Professor McSnurp is Professor McGonagall, Professor Sprout is Professor Stikling and Gilderoy Lockhart becomes Gyldeprinz Gulmedal (lit. ‘Goldprince Goldmedal’) and Hagrid is Gygrid and Dobby the House-elf is Noldus. The Dursleys, who live in Hekkveien 4 (4 Privet Drive), are called Wiktor, Petunia and Dudleif Dumling (dum = dumb, stupid). The Weasleys are called Wiltersen in Norwegian, so Ron is Ronny Wiltersen, Ginny is Gulla, Percy is Perry and Fred and George are Fred og Frank! Hermione Granger is Hermine Grang, Nilus Langballe is Neville Longbottom and Draco Malfoy is Draco Malfang. Diagon Alley is Diagonallmenningen, Knockturn Alley is Spindelsmuget and the shop ‘Flourish and Blotts’ is ‘Snirckel & Blaek‘ (from blekk = ink). The bank Gringotts becomes Flirgott. The Burrow is Hiet and The Leaky Cauldron is Den lekke heksekjel. The 4 Hogwarts houses are: Gryffindor Griffing, Hufflepuff Håsblås, Ravenclaw Ravnklo and Slytherin Smygard.

Danish

The Danish Hogwarts is called Hogwarts Skole for Heksekunster og Troldmandsskab. Diagon Alley is Diagonalstræde (Diagonalstræde is not a pun in Danish, though) and Knockturn Alley is rendered as Tusmørkegyden (lit. ‘Twilight Alley’) . The Burrow becomes Vindelhuset (‘the spiral house’), The Leaky Cauldron is Den Utætte Kedel and Gringotts is called Gringotts Troldmandsbank. The Owlery is Ugleriet. The ghost Moaning Myrtle is Hulkende Hulda. House elves are husalfer. Professor Sprout is called Professor Spire and Gilderoy Lockhart is Glitterik Smørhår (lit. Glittery Butterhair). Professor Horatio Schnobbevom is Horace Slughorn. The subject Divination is Spådom and the art of Apparition is called Spektral Transferens.

Swedish

In Swedish, Hogwarts is called Hogwarts skola för häxkonster och trolldom, Diagon Alley is Diagongränden, Knockturn Alley becomes Svartvändargränden (lit. ‘Blackturner Alley’), the wizarding bank Gringotts is Gringotts trollkarlsbank (or just simply Gringotts). The pub The Leaky Cauldron is Den Läckande Kitteln and The Burrow is Kråkboet (lit.’Crow’s Nest’). The Death Eaters are the Dödsätare and the Sorting Hat is en sorteringshatt. The subject Spådomskonst is divination and Potions is Trolldryckskonst. 12 Grimmauld Place is Grimmaldiplan nummer 12 (the pun in English – ‘grim old place’ – is lost here in the translation) and the Forbidden Forest is Den mörka skogen. The young Voldemort Tom Riddle is called Tom Gus Mervolo Dolder. Bill and Fleur Weasley’s house, The Shell Cottage, is Snäckstugan in Swedish.

If you like the paper Hogwarts castle in this article, it can be purchased on Amazon here: ‘Build your own Hogwarts castle!‘ (ISBN 978-1535422352) http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/1535422351

Vocabulary: The Environment in Norwegian, Danish and Swedish

Today’s blog post will take us to Scandinavia, and to some thematic vocabulary about a topic of current importance, namely the environment, in Swedish, Danish and Norwegian.

Norwegian/Norsk

Miljøet = the environment

globale oppvarming = global warming

Klimaendringen = climate change

Drivhuseffekten = Greenhouse Effect

utslipp av karbondioksid = carbon dioxide emissions

drivhusgasser = greenhouse gases

havnivåstigningen/ Havnivåendring = sea level rise

økosystemet = ecosystem

biologisk mangfoldet = biodiversity

en truet art = a threatened species

ørkendannelse = desertification

en regnskog = rainforest

avskogningen = deforestation

forurensningen = pollution

sur nedbør = acid rain

holdbar = sustainable

fornybar = renewable

fornybar energy = renewable energy

bærekraft = sustainability

Danish/Dansk

Miljøet = the environment

global opvarmning = global warming

Klimaændringen = climate change

Drivhuseffekten = Greenhouse Effect

Kuldioxidudslippet = carbon dioxide emissions

Drivhusgasser = greenhouse gases

stigende vandstand i havene = sea level rise

økosystemet = ecosystem

biodiversitet = biodiversity

en truet art = a threatened species

ørkendannelse = desertification

en regnskov = rainforest

skovrydningen = deforestation

forureningen = pollution

syreregn = acid rain

bæredygtig = sustainable

Vedvarende = renewable

vedvarende energi = renewable energy

bæredygtighed = sustainability

Swedish/Svenska

Miljön = the environment

Global uppvärmning = global warming

Klimatförändringen = climate change

Växthuseffekten = Greenhouse Effect

Koldioxidutsläppet = carbon dioxide emissions

Växthusgaser = greenhouse gases

höjning av havsnivån/havsnivåhöjning = sea level rise

ekosystemet = ecosystem

den biologiske mångfald = biodiversity

en hotad art = a threatened species

ökenspridningen = desertification

en regnskog = rainforest

avskogningen/skogskövlingen = deforestation

miljöförstöring = pollution

surt regn = acid rain

hållbar = sustainable

förnybar = renewable

förnybar energi = renewable energy

hållbarhet = sustainability

Colour perception in various languages

Today’s blog post will be about colour perception in different cultures and languages around the world.

The terms for colours cannot always be translated in a straightforward manner since some colours, esp. green and blue (“grue”) in some Asian languages, are often perceived differently from those in the West, and are considered separate colours in those countries whereas in English there is just one term for both shades or vice versa.

Russian

In Russian, there are two different terms for blue which are considered as separate colours and not just as shades of the same colour as in English: голубой (‘goluboy’) light blue and синий (‘siniy’) dark blue.

Hungarian

In Hungarian, there are two separate terms for red: piros is a bright red and vörös is a dark red.

German

In German, there are two different terms for pink: Pink is the same bright saturated shade as in English, but when the colour is pale pink it is called rosa.

‘Grue’ or green and blue in various Asian languages

The origin of the perception of a green-blue (‘grue’) colour, which in English is called ‘teal’ or is seen as two separate colours (blue and green), comes from the Chinese character 青 (qīng).

The colour qīng 青 can mean either of the colours that in English are referred to as ‘green’, ‘blue’, or ‘black’, depending on the context and the nouns or fixed phrases it is used with. To give an example, qing means ‘blue’ when used with ‘sky’ 青天 (qīngtiān) or ‘eyes’青眼 (qīngyǎn) , but ‘black’ when used with ‘hair’ 青丝(qīngsī) and ‘green’ when used with the character for ‘mountain’ 青山 (qīngshān), ‘grass’青草 (qīngcǎo) or ‘vegetables’ 青菜 (qīngcài).

Qing 青 , according to tradition, is the colour of things that are born and the term 青春 (qīngchūn ‘green spring’) means youth. This is connected to its meaning ‘black’ since young people in China have dark hair, or 青鬓 (qīng bìn) ‘black temple hair’, an idiom referring to young people. Qing can also refer to black clothes or fabrics and one of the main female roles in Chinese opera, 青衣 (qīngyī), refers to the fact that most actors wear black clothing.

Qing can also refer to the colour ‘blue’, which originates from the dye bluegrass which in ancient times was used to dye things in the colour of qing. The idiom 青出於藍,而勝於藍/青出于蓝,而胜于蓝 (qīngchūyúlán ér shèng yú lán, ‘blue comes from the indigo plant but is bluer than the plant itself’) describes how a student could come to excel their teacher.

The character 青qing originally derives from the components for 生 ’growth of plants‘ and 丹 ’cinnabar‘, which was also used for dyeing and by extension came to refer to ‘colour’ in general, so 青qing came to be known as the ‘colour of growing plants’ and green-blue, and came to describe a range of colours from light green through blue to deep black 玄青 (xuánqīng). Over time, the character for cinnabar was exchanged with the similar character for ‘moon’月.

The modern Mandarin Chinese language, however, also has the blue–green distinction with 蓝/ 藍 lán for blue and 绿 / 綠 lǜ for green. Another peculiarity of Chinese colour perception is the case of ‘red’ 红 / 紅, hóng and ‘pink’ 粉红, fěn hóng (lit.’powder red’), which are considered varieties of a single colour.

青 qing (Cantonese 廣東話 )

In Cantonese, qing 青 can describe the same range of colours as in Mandarin Chinese. It means ‘green’ when referring to grass, plants or the mountains, ‘blue’ when referring to the sky or stones, and ‘black’ or ‘young’ when referring to hair or fabrics. However, in Cantonese (廣東話), 青 qing meaning ‘black’ is still used in contexts where the use of 黑 would be inauspicious since it is a homophone of ‘乞’ (beggar), for example 黑衣, ‘black clothes’, would also mean ‘beggar’s clothes’.

Vietnamese

Vietnamese has taken over the green-blue colour perception from the ancient Chinese character 青 and is read as xanh, which can mean both ‘green’ or ‘blue’ depending on the context. To specify which shade exactly you mean, you have to add some descriptive terms, so xanh da trời means ‘blue as the sky’, xanh dương or xanh nước biển means ‘blue as the ocean’ and xanh lá cây means ‘green like the leaves’. Vietnamese sometimes uses the terms xanh lam for blue and xanh lục for green, which derive from the Chinese characters 藍and 綠 respectively.

Japanese

Also Japanese has the colour green-blue, or ao 青 (hiragana あお, romaji ao, historical hiragana あを), which also derives from the ancient Chinese character and its connotations. So ao 青 can mean ‘blue’, ‘green’ or ‘black’ depending on the context. In the case of Japanese, the colour connotation ‘black’ comes from the bluish-black colour of a horse’s hair. Ao is also used in particular to refer to the green of traffic lights and to the colour of plant leaves, vegetables and apples. By contrast, other ‘green’ objects will generally be referred to as being 緑 midori, e.g. clothes, cars, etc.

Lakota

Also in the native American language Lakota (‘Sioux’), one word is used for both blue and green, namely the term tȟó. However, a term for ‘green’ – tȟózi- has come into use, which is made up of the terms tȟó meaning ‘blue-green’ and zí meaning ‘yellow’. In the same way, zíša/šázi refers to the colour orange, šá on its own meaning ‘red’. The colour purple or violet is thus šátȟo/tȟóša.

Some interesting links for further reading on the topic:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue%E2%80%93green_distinction_in_language

http://www.theworldofchinese.com/2013/06/what-color-is-qing/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E9%9D%92

Does your language also have a different colour perception from the English one? Let us know in the comments!! 🙂

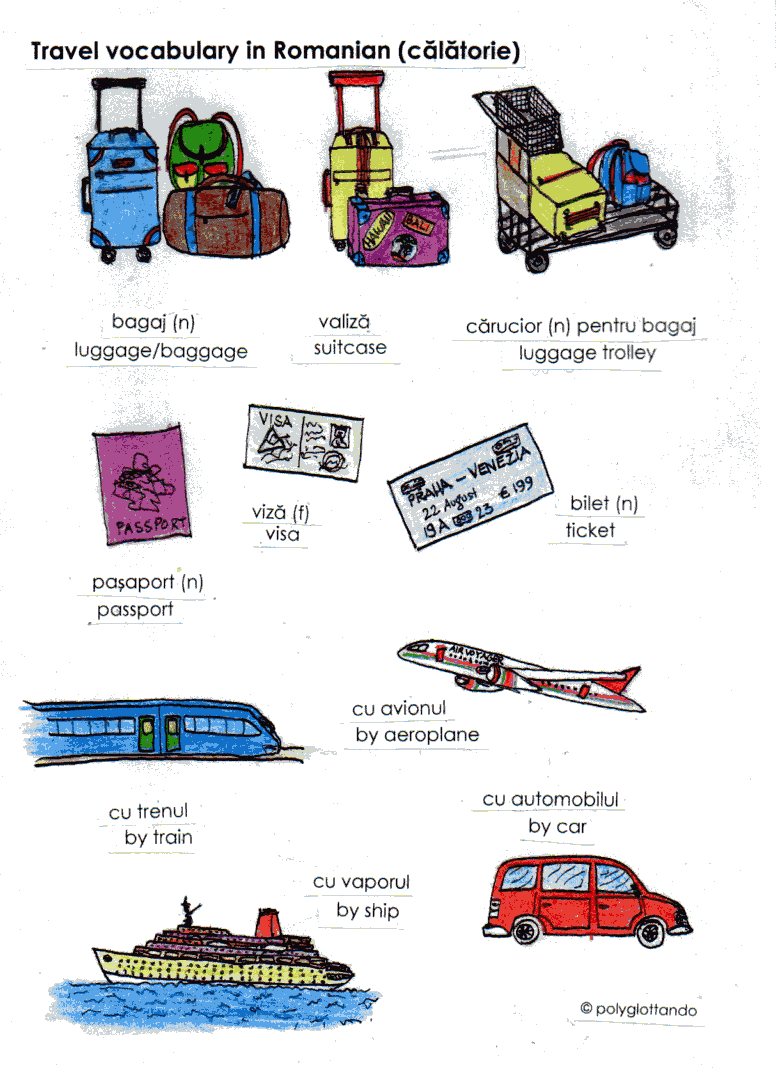

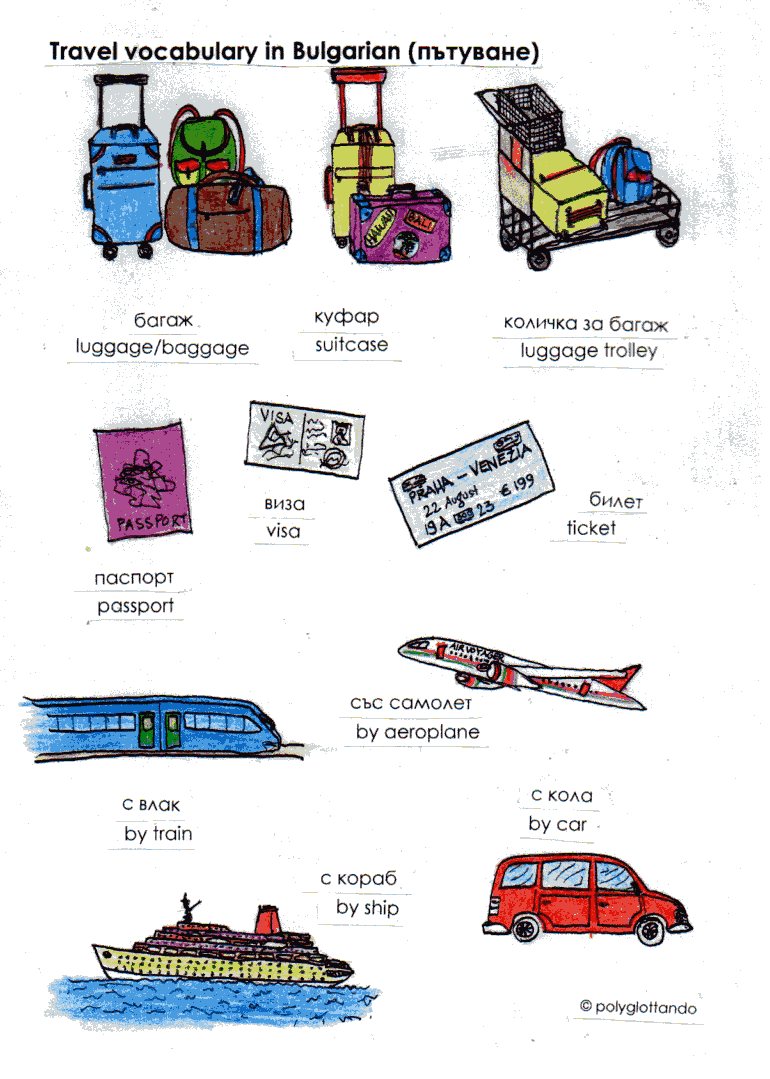

Vocabulary: ‘traveling’ in Bulgarian and Romanian

Today’s blog post is going to take us to South Eastern Europe again, namely to Bulgaria and Romania. Since the traveling and holiday season is about to start for many people, we will look at some travel-related vocabulary in Romanian and Bulgarian. Romanian is a Romance language, of course, while Bulgarian is a Slavonic language, so the two are not related.

How to create a language immersion environment (or a day in the life of a polyglot)

The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563

Today’s blog post is about how to create a language immersion environment at the place where you live, which will permit you to learn your target language(s) naturally by ‘absorbing’ them in your daily life. Learning a language to fluency is perfectly possible even if you cannot travel to the country where it is spoken and spend some longer periods of time there. I personally learned all of my languages from abroad and never in the countries where they are spoken (with exception of my two second languages), and I have done so via an immersive environment which I created for myself. This is not difficult and to illustrate how it can be done, I will describe a ‘typical’ week in my life in the following paragraphs. 🙂

To start with, I have to say that I am a freelancer with several, very different, jobs, so each day I have to perform quite different tasks which permit me to integrate my language practice to a greater or lesser extent into my daily routine, depending on which task is due on a particular day. One thing I virtually never ever (!!) do is sitting at a desk studying a language from a textbook! My daily language learning routine is completely integrated into my daily life and cannot be separated from it – I virtually live my life in the different languages I speak 🙂 . In this way, I also manage to practice (and learn) my languages for about more than 20 or 30 hours each week.

So how do I integrate my language learning into my daily life? On a typical day, one of the first things I do each morning is to study my current main target languages from a textbook for about 15-30 minutes, sometimes longer, even before getting up properly. While getting ready for the day, I usually learn some new vocabulary in the otherwise ‘lost’ time (= while making breakfast, getting dressed, etc.) – in my opinion it is the most time-efficient way of learning vocabulary . 🙂

Often, when my work for that day permits it, I also hone my language skills while working: Especially good for language practice are days on which I have to perform ‘manual’ tasks which leave my mind free to wander, like illustrating, or designing or making/assembling new products. This often gives me the opportunity to listen to language tapes in various languages for several hours at a time while working. Sometimes, my work also involves customer service for a small business I work for, and this correspondence will then be in any language the customer has chosen to write in – another opportunity to practice my skills. So if your work permits it and you want to integrate more language practice into your daily life, try listening to language tapes while you work instead of to the radio or to music (unless they are in one of your target languages of course 🙂 ). On other days, for example when I have to work on machines which are too loud to permit the use of audiotapes, I usually learn vocabulary while working. So during an average workday, I can often integrate quite a substantial amount of extra learning practice, though not always.

In my free time, I continue learning and using my languages, both directly and indirectly. A language learning practice I really do every single day (!!) is listening to the Word of the Day online, in about 40 languages (in every language for which I have found a daily post!) . This takes me about an hour, on the average 1-2 minutes for each language. This might not seem like much, but this adds up quite substantially over the course of a month and a year: 1-2 minutes per day per language means at least (!!) 7-15 minutes of language practice per week in each of these c.40 languages, and again at least 30-60 minutes of practice per month for each language, etc.! Then, I have recently joined duolingo, which is quite fun, and where I have signed up for the intensive streak of 5 exercices per day, but I usually do more than that since it is quite addictive 🙂 . So there I spend another hour or so practising languages, learning new ones as well as using it to brush up old ones.

Internet: This is another great opportunity if you want to immerse yourself in your target languages. Whenever I use twitter, I log in using a different language each time. 🙂 Both my twitter and facebook feeds are multilingual themselves (!!) – I pursue my hobbies in my various languages! So I do not only follow and read posts about learning languages, but I subscribe to pages about my various interests in a variety of languages, so that my newsfeed is totally multilingual. To illustrate this, if your interest is kittens for example 😉 , search for facebook pages about kittens in the languages you are learning .and subscribe to them, if your interest is politics, subscribe to political pages from various countries, etc. So in this way you can both pursue an interest that personally captivates you while practising your target languages at the same time. This is what immersion is all about, namely that language learning cannot be distinguished from ordinary life any more and that you start to live your life in the languages. 🙂

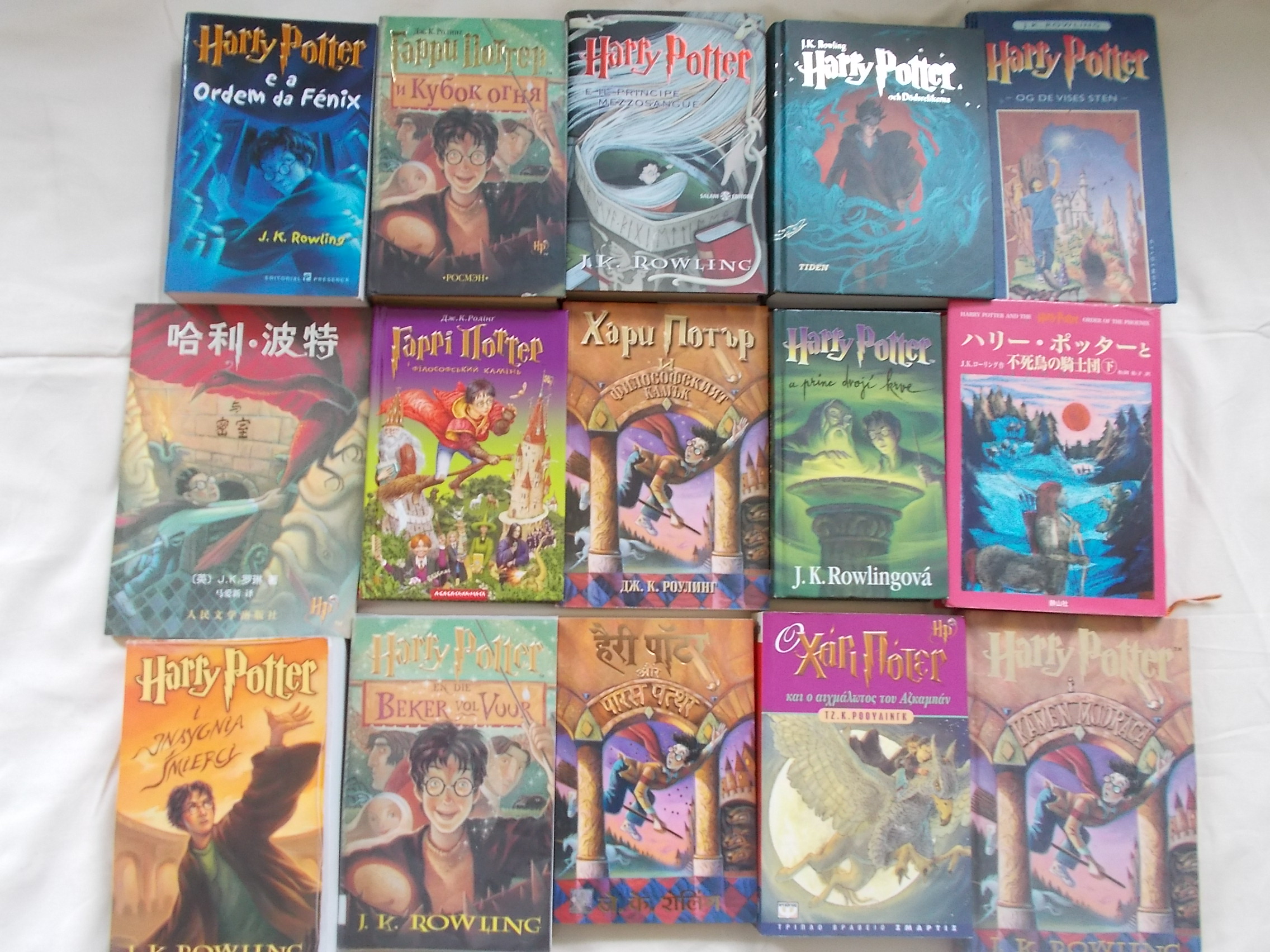

My final language practice of an average day takes place at night. I don’t have a TV, so I never watch movies every night like most people do. Instead, I enjoy reading. Often, I spend another 30 minutes or an hour working through a textbook (on nights with plenty of time) or just reading (in any language). But each night before going to bed, I read the Harry Potter books for at least an hour, usually in one of my intermediate-level languages to take them to a higher level eventually. (See a previous blog post of mine on how you can use the Harry Potter books or any other novels to boost your intermediate language skills). So on an average day, I manage to immerse myself in my languages at the very least for 3 or 4 hours, if not more. 🙂 And this time is NOT spent studying at a desk 🙂 .

I rarely watch movies, but if I do, I get myself a DVD and watch it in my target language. If I am proficient in the language, I use no subtitles, but if it is in one of my intermediate languages, I usually turn on the subtitles in the target language (NOT in English!!) so I can read along if I don’t understand something. I find this really helps to improve my skills. Another thing I do very frequently is just listening to films (usually documentaries, which I prefer) while working on the computer. Mostly I don’t need to see the pictures or the footage, and this is a great way of honing my listening comprehension. 🙂

As you can see, language immersion does not require you to actually live in the countries to be immersed in the language, you just have to create an environment in your daily life in which you live your life in the language.

How to improve your intermediate reading comprehension through parallel reading of literature

Today’s blog post is about how you can magically improve and boost your intermediate reading comprehension through parallel reading of literature, e.g. the ‘Harry Potter’ books 🙂 .

All you need is a book in your target language and the same book in your native language (or in another language you are very proficient and advanced in) as well as two bookmarks, so you can read them in parallel. This will make a dictionary redundant.

I personally collect the ‘Harry Potter’- books in all languages, but not as a “collector’s item” but actually to read them in these languages. The ‘Harry Potter’-books are great to improve your reading comprehension especially in ‘minor’ languages, since they are often available even in smaller languages where it is otherwise virtually impossible to get hold of literature in the language unless you travel to the country and bring them home with you. But you can use virtually any book in your target language for which you can get a copy also in your native language. However, popular books like bestsellers, the ‘Harry Potter’-series or ‘Le Petit Prince‘ (The Little Prince) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, that are collected even by people who cannot speak the languages, are best since they are widely available in many languages (even though they may often be quite expensive!).

So how does this method, parallel reading, work? Basically, you have both books open at the same page and read them alongside each other. However, in order to be efficient to improve your existing intermediate reading skills, you ought to read the text in your target language first, and only check the book in your native language when you really don’t understand something. Done persistently and regularly, this will soon boost your reading skills and you don’t need a dictionary for it.

Another way in which parallel reading can be highly instructive is in comparative reading of both texts. For this, you read each sentence in sequence, first in your target language, then in your native language, all the while comparing how each expression is translated and rendered in your target language. This will not only teach you useful expressions, but it will also teach you something about the translating process. It will also make you familiar with the way sentences are structured in your target language, which can be highly valuable.

Where can you find popular books like the Harry Potter-series or Le Petit Prince in many languages? If you have any second-hand or antiquarian bookstores near where you live, it is always worth a visit going there first to see if they might not have the title you are looking for, as they might be considerably cheaper if bought used, apart from being better for the environment, especially since you need the book also in your native language. If you don’t have any such bookstore near where you live or they do not have your title, try to search on Amazon: type in the title plus ‘in [insert target language of your choice]’, e.g. ‘Harry Potter in Spanish’ or ‘Harry Potter Spanish version/edition’. This ought to bring up some results for many, though unfortunately not for all, languages. 🙂

Do you also collect a certain series of books or a book from a certain author which you like to read in a foreign language? Tell us about it in the comments! 🙂

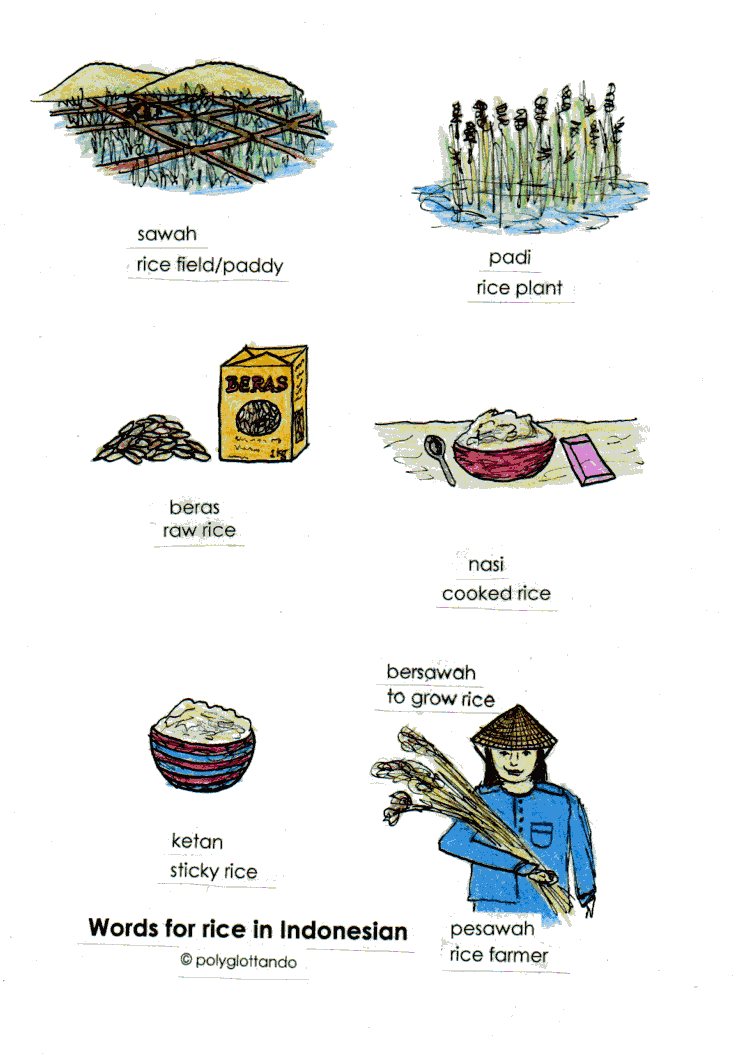

Vocabulary: ‘Rice’ in Indonesian and Asian languages

Today’s blog post is taking us to Asia again, to Indonesia and Japan and China, and to the various words for ‘rice’. Unlike in western languages, where there is just one word for any type of rice, in many Asian languages, there are different terms for ‘rice’ depending on what condition the rice is in, i.e. whether it is raw grains, cooked rice or still a rice plant.

In Balinese (Basa Bali) the various term for ‘rice’ are:

Pantun = rice plant (indon. padi)

sawah or manik galih = rice field/paddy

beras or baas = raw rice, rice grains

nasi = cooked rice

ketan = sticky rice

The Indonesian word for ‘rice plant’, padi, is the origin of the English term for paddy field. 🙂

There are also different words for ‘rice’ in Japanese and Chinese (Mandarin).

In Japanese, these are:

稲 ine =rice plant

米 kome = rice grains, uncooked rice

白米 hakumai = white rice, polished rice

籾 momi = rough rice

玄米 genmai = brown rice, unpolished rice

ご飯 gohan = cooked rice

餅米 mochigome = sticky rice

水田suiden = paddy field, rice field

And the Chinese terms for different kinds of rice are:

米饭 Mǐfàn = cooked rice

大米 Dàmǐ = raw rice

糯米饭 Nuòmǐ fàn = sticky rice

稻田 Dàotián = paddy field, rice field

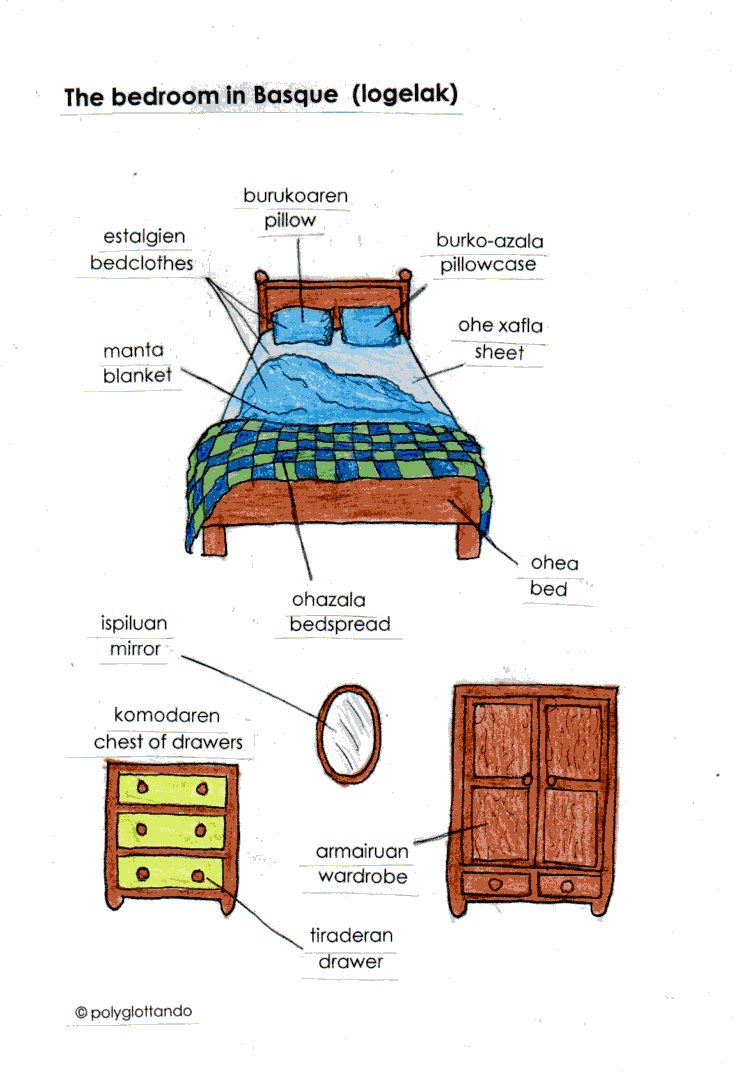

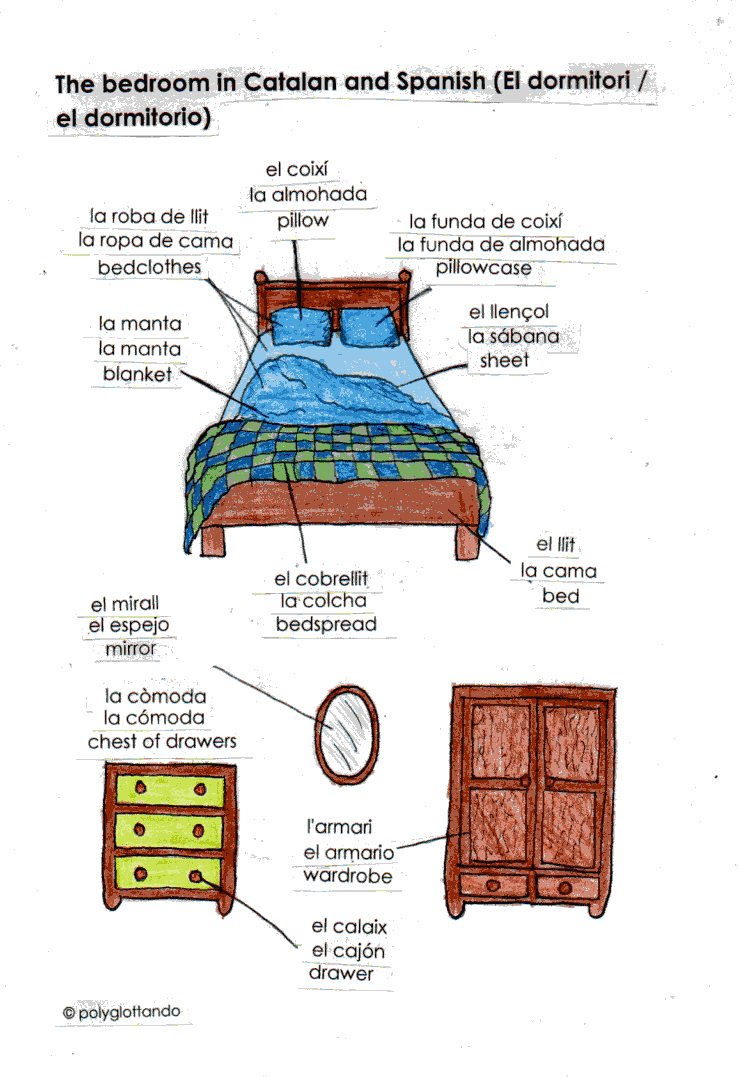

Vocabulary: The bedroom in Catalan and Basque

Today we continue our series of comparing vocabulary of a geographic region. We are going to Spain again, and to be more exact, to the minority languages spoken there, Catalan (Català) and Basque (Euskara). Both Catalan and Basque are also spoken in the South of France in the areas bordering Spain. Basque is an isolate language that is unrelated to any other language and it is believed to be one of the few surviving pre-Indoeuropean languages of Europe. Catalan is a Romance language and is basically a mix of both Iberian-Romance and Gallo-Romance influences, since it shares vocabulary and grammatical features with both Spanish and French.