Today’s blog post is taking us to South East Asia, to the Indonesian island of Bali and its language, Basa Bali. Balinese is an Austronesian language, like Indonesian, and is spoken by about 3 million people on the island of Bali and in parts of Indonesia like western Lombok and some villages in Sulawesi, where many Balinese anak Bali live. Virtually all people in Bali also speak Bahasa Indonesia, the national language, except for some old people. While the grammatical structures of Indonesian and Balinese are quite similar, the vocabulary of both languages is quite different. Balinese has many words of Sanskrit, Farsi, Tamil as well as Javanese, Dutch and Portuguese origin, reflecting the Hindu background of Balinese society. A particularity of Balinese is its two levels of social distinction, which each has its own set of parallel vocabulary and which reflect both the social status of the speaker as well as that of the person addressed. Biasa or common words are used by people of equal social status and they reflect informality and intimacy among the speakers. In contrast, halus or refined words reflect formality and distance among the speakers. There are, however, only a certain number of words that are different in both language levels, mainly those concerning human beings, while most words can be used for both levels. Topics that are considered very halus, like religion, always require the use of halus words. The Balinese are predominantly Hindus and the traditional Balinese social structure is therefore based on the Hindu caste system. However, ‘caste’ in Bali is not at all based on rigid distinctions and restrictions of occupations as in India, it merely reflects a notion of general social status, which in turn is reflected in the language. The 4 castes are:

Today’s blog post is taking us to South East Asia, to the Indonesian island of Bali and its language, Basa Bali. Balinese is an Austronesian language, like Indonesian, and is spoken by about 3 million people on the island of Bali and in parts of Indonesia like western Lombok and some villages in Sulawesi, where many Balinese anak Bali live. Virtually all people in Bali also speak Bahasa Indonesia, the national language, except for some old people. While the grammatical structures of Indonesian and Balinese are quite similar, the vocabulary of both languages is quite different. Balinese has many words of Sanskrit, Farsi, Tamil as well as Javanese, Dutch and Portuguese origin, reflecting the Hindu background of Balinese society. A particularity of Balinese is its two levels of social distinction, which each has its own set of parallel vocabulary and which reflect both the social status of the speaker as well as that of the person addressed. Biasa or common words are used by people of equal social status and they reflect informality and intimacy among the speakers. In contrast, halus or refined words reflect formality and distance among the speakers. There are, however, only a certain number of words that are different in both language levels, mainly those concerning human beings, while most words can be used for both levels. Topics that are considered very halus, like religion, always require the use of halus words. The Balinese are predominantly Hindus and the traditional Balinese social structure is therefore based on the Hindu caste system. However, ‘caste’ in Bali is not at all based on rigid distinctions and restrictions of occupations as in India, it merely reflects a notion of general social status, which in turn is reflected in the language. The 4 castes are:

Brahmana , the highest caste and those of priests (Brahmin in India), the name of members of this caste starts with Ida Bagus (m) or Ida Ayu (f);

ksatria the second caste and ruler and warrior caste (Kshatriya in India), the name of members of this caste starts with Anak Agung or Cokorda/Tjokorde Gde (m) or Tjokorde Istri (f);

wesia the third caste and that of merchants and officials (weysha in India), the name of members of this caste starts with I Gusti ;

and the sudra or rice farmers’ caste (shudra in India, the non-caste). Only about 7 % of the anak Bali belong to the triwangsa or the three higher castes, while the large majority, more than 90%, belong to the sudra caste.

Generally, people of a lower caste will ‘speak upward’ to a member of a higher caste, i.e. they will choose the more refined halus words. Likewise, a member of a higher caste will ‘speak down’ to a member of a lower class, that is, choose the common biasa words. So a farmer speaking to another farmer would use biasa words, and a member of a high caste speaking with another high class individual would use halus words. However, a farmer speaking with or referring to a member of the high class would use halus words.

Here is an example:

Biasa level: Dadi tawang adane? May I know your name? (Indonesian: Bisa saya tahun nama Anda?) Adan tiange…. Jerone nyen? My name is…. What’s yours? (Indonesian: Nama saya….. Anda siapa?)

Halus level: Dados uningin parabe? May I know your name? (Indonesian: Bisa saya tahun nama Anda?) Parab tiange….. Sira parab jerone? My name is…. What’s yours? (Indonesian: Nama saya…. Anda siapa?)

Biasa level: Ene poh. Luung sajan. (Indonesian: Ini mangga. Bagus sekali.) This is a mango. It is very good. Ene biu. (Indonesian: Ini pisang) This is a banana.

Halus level: Niki poh. Becik pisan. (Indonesian: Ini mangga. Bagus sekali.) This is a mango. It is very good. Niki pisang. (Indonesian: Ini pisang) This is a banana.

As you can see from the last example, there are often two different words for the same thing, like here the word for ‘banana’ which is biu on the biasa level, but pisang on the halus level of speech. The same thing is true for the expression ‘This is….’, which is ‘niki…..’ on the halus level, but ‘ene…’ on the biasa speech level.

Author: chensiyuan, wikipedia Commons

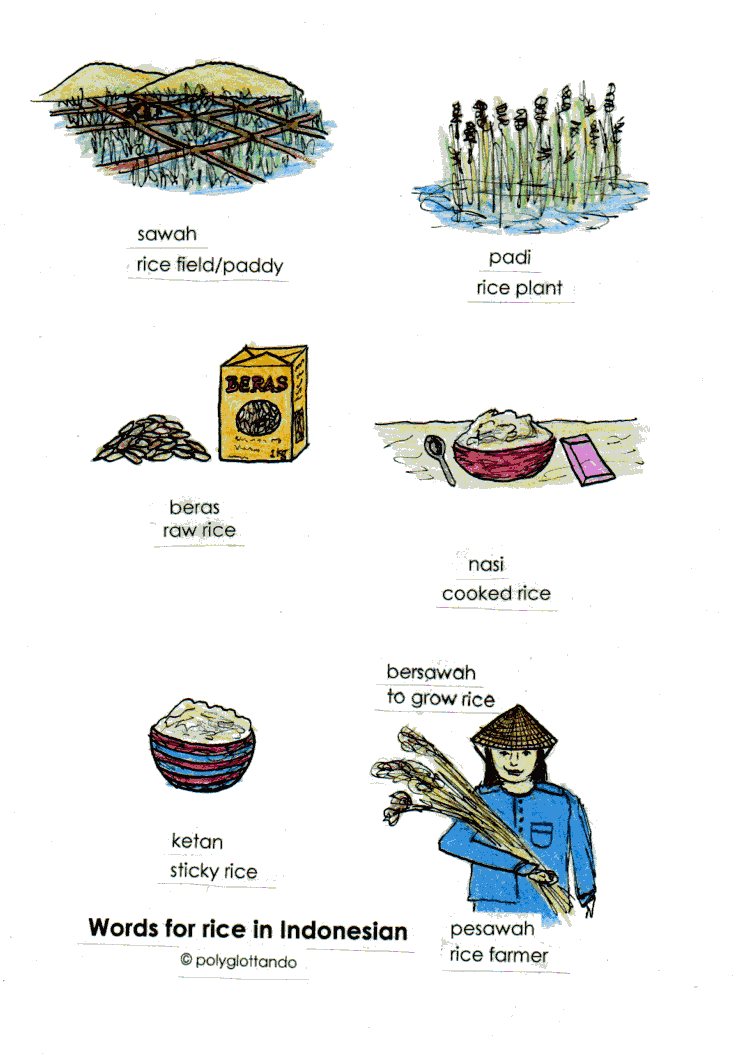

Here are some words typical of Balinese culture:

Odalan temple festival (halus word only)

Pedanda Brahmana priest (pandit in India)

Meru wooden, pagoda-like building with grass roof, named after the holy Mount Meru in India

Naga mythological snake or dragon

Pura puseh temple for the divine ancestors

Pura dalem temple for the dead in the underworld

Another particularity of the Balinese is that people are named according to their order of birth in their family. The names are the same for both males and females, but as an indicator of gender the particle i is used for males and ni for females before the name. Here are the names for members of the farmer caste:

Wayan for the first-born of a family (I Wayan/ Ni Wayan)

Made for the second child

Nyoman for the third child Ketut for the fourth child

A further cultural peculiarity is that the anak Bali will always give directions according to the four directions of the compass instead of using ‘left’ and ‘right’.

North = kaja South = kelod West = kauh East = kangin (all biasa words)

This has interesting implications: While kaja generally means ‘inland, towards the mountains’ ‘in the direction of Gunung Agung‘, the highest and holy mountain of Bali (a prosperous direction), in Southern and Central Bali it therefore means ‘north’ but in Buleleng in Northern Bali it means ‘south’! The same goes for kelod, which means ‘towards the sea’ (a disastrous direction): in Southern and Central Bali it refers to the ‘south’, while in Buleleng in Northern Bali it means ‘north’!

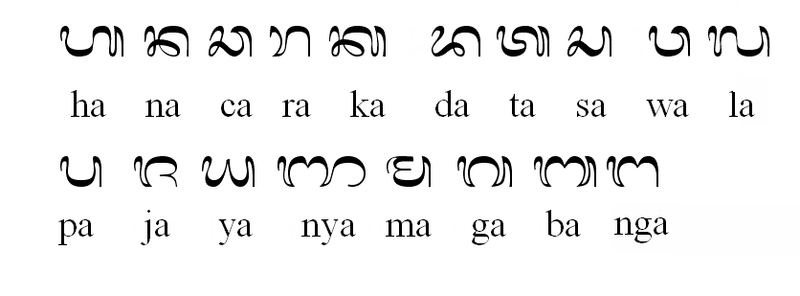

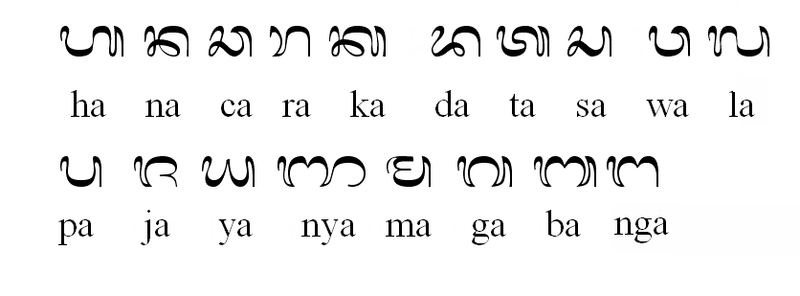

Balinese also has an old indigenous script, the Carakan script:

the old Balinese script, the Carakan alphabet

Bali also has a very rich mythology. According to the Balinese creation myth, in the beginning of time, only the world snake Antaboga existed. During a meditation, Antaboga created Bedawang or Bedawang Nala, a giant turtle who carries the world on her back. Two snakes or dragons (naga) lie on Bedawang’s shell, as well as the Black Stone, which is the lid of the underworld. All other creations sprang from Bedawang. When Bedawang moves, there are earthquakes and volcanic eruptions on earth.

Bedawang = boiling water Nala = fuel

Bidawang means ‘turtle river’ in the Banjar language

The goddess Setesuyara and the god Batara Kala, the creator of light and earth, rule over the underworld. Above the world, there is first a layer of water, then a layer of moving sky, where Semara, the god of love lives. Above this floating sky there is the dark blue sky with the sun and the moon. Yet again above this sky, there is the scented sky full of fragrant flowers, the abode of the human-headed bird Tjak (Cak), of the snake Taksaka and of the Awan-snakes (falling stars). The ancestors live in a fiery sky, located above the scented sky. The abode of the gods forms the final and uppermost layer of the sky.

Etymology: a = not, Ananta = endless, never exhausted, boga = food

Anantaboga = endless food, food that never gets exhausted

A rather good online dictionary for Balinese: http://dictionary.basabali.org/Main_Page

Author: Tropenmuseum Amsterdam, Wikipedia Commons

the turtle Bedawang Nala and the snake Ananthabhoga

Author: Tropenmuseum, Wikipedia Commons

Wayang figure representing Batara Kali