Today’s blog post will be about colour perception in different cultures and languages around the world.

The terms for colours cannot always be translated in a straightforward manner since some colours, esp. green and blue (“grue”) in some Asian languages, are often perceived differently from those in the West, and are considered separate colours in those countries whereas in English there is just one term for both shades or vice versa.

Russian

In Russian, there are two different terms for blue which are considered as separate colours and not just as shades of the same colour as in English: голубой (‘goluboy’) light blue and синий (‘siniy’) dark blue.

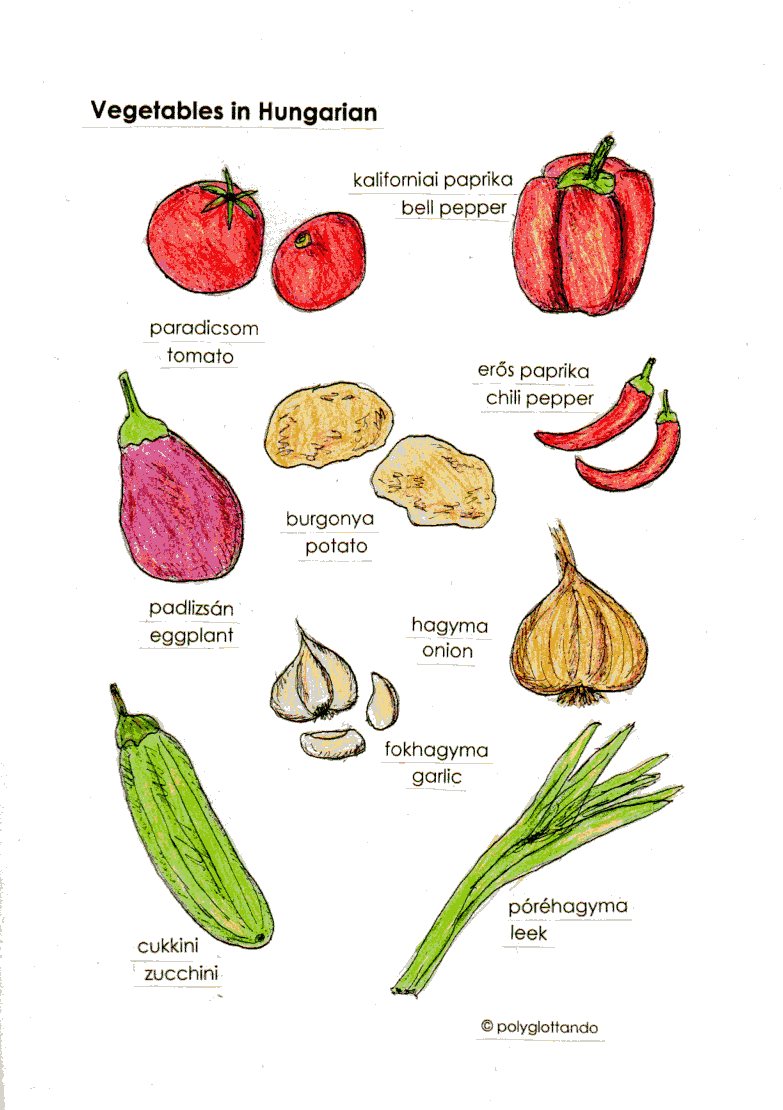

Hungarian

In Hungarian, there are two separate terms for red: piros is a bright red and vörös is a dark red.

German

In German, there are two different terms for pink: Pink is the same bright saturated shade as in English, but when the colour is pale pink it is called rosa.

‘Grue’ or green and blue in various Asian languages

The origin of the perception of a green-blue (‘grue’) colour, which in English is called ‘teal’ or is seen as two separate colours (blue and green), comes from the Chinese character 青 (qīng).

The colour qīng 青 can mean either of the colours that in English are referred to as ‘green’, ‘blue’, or ‘black’, depending on the context and the nouns or fixed phrases it is used with. To give an example, qing means ‘blue’ when used with ‘sky’ 青天 (qīngtiān) or ‘eyes’青眼 (qīngyǎn) , but ‘black’ when used with ‘hair’ 青丝(qīngsī) and ‘green’ when used with the character for ‘mountain’ 青山 (qīngshān), ‘grass’青草 (qīngcǎo) or ‘vegetables’ 青菜 (qīngcài).

Qing 青 , according to tradition, is the colour of things that are born and the term 青春 (qīngchūn ‘green spring’) means youth. This is connected to its meaning ‘black’ since young people in China have dark hair, or 青鬓 (qīng bìn) ‘black temple hair’, an idiom referring to young people. Qing can also refer to black clothes or fabrics and one of the main female roles in Chinese opera, 青衣 (qīngyī), refers to the fact that most actors wear black clothing.

Qing can also refer to the colour ‘blue’, which originates from the dye bluegrass which in ancient times was used to dye things in the colour of qing. The idiom 青出於藍,而勝於藍/青出于蓝,而胜于蓝 (qīngchūyúlán ér shèng yú lán, ‘blue comes from the indigo plant but is bluer than the plant itself’) describes how a student could come to excel their teacher.

The character 青qing originally derives from the components for 生 ’growth of plants‘ and 丹 ’cinnabar‘, which was also used for dyeing and by extension came to refer to ‘colour’ in general, so 青qing came to be known as the ‘colour of growing plants’ and green-blue, and came to describe a range of colours from light green through blue to deep black 玄青 (xuánqīng). Over time, the character for cinnabar was exchanged with the similar character for ‘moon’月.

The modern Mandarin Chinese language, however, also has the blue–green distinction with 蓝/ 藍 lán for blue and 绿 / 綠 lǜ for green. Another peculiarity of Chinese colour perception is the case of ‘red’ 红 / 紅, hóng and ‘pink’ 粉红, fěn hóng (lit.’powder red’), which are considered varieties of a single colour.

青 qing (Cantonese 廣東話 )

In Cantonese, qing 青 can describe the same range of colours as in Mandarin Chinese. It means ‘green’ when referring to grass, plants or the mountains, ‘blue’ when referring to the sky or stones, and ‘black’ or ‘young’ when referring to hair or fabrics. However, in Cantonese (廣東話), 青 qing meaning ‘black’ is still used in contexts where the use of 黑 would be inauspicious since it is a homophone of ‘乞’ (beggar), for example 黑衣, ‘black clothes’, would also mean ‘beggar’s clothes’.

Vietnamese

Vietnamese has taken over the green-blue colour perception from the ancient Chinese character 青 and is read as xanh, which can mean both ‘green’ or ‘blue’ depending on the context. To specify which shade exactly you mean, you have to add some descriptive terms, so xanh da trời means ‘blue as the sky’, xanh dương or xanh nước biển means ‘blue as the ocean’ and xanh lá cây means ‘green like the leaves’. Vietnamese sometimes uses the terms xanh lam for blue and xanh lục for green, which derive from the Chinese characters 藍and 綠 respectively.

Japanese

Also Japanese has the colour green-blue, or ao 青 (hiragana あお, romaji ao, historical hiragana あを), which also derives from the ancient Chinese character and its connotations. So ao 青 can mean ‘blue’, ‘green’ or ‘black’ depending on the context. In the case of Japanese, the colour connotation ‘black’ comes from the bluish-black colour of a horse’s hair. Ao is also used in particular to refer to the green of traffic lights and to the colour of plant leaves, vegetables and apples. By contrast, other ‘green’ objects will generally be referred to as being 緑 midori, e.g. clothes, cars, etc.

Lakota

Also in the native American language Lakota (‘Sioux’), one word is used for both blue and green, namely the term tȟó. However, a term for ‘green’ – tȟózi- has come into use, which is made up of the terms tȟó meaning ‘blue-green’ and zí meaning ‘yellow’. In the same way, zíša/šázi refers to the colour orange, šá on its own meaning ‘red’. The colour purple or violet is thus šátȟo/tȟóša.

Some interesting links for further reading on the topic:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue%E2%80%93green_distinction_in_language

http://www.theworldofchinese.com/2013/06/what-color-is-qing/

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E9%9D%92

Does your language also have a different colour perception from the English one? Let us know in the comments!! 🙂