Today’s blog post is taking us to Japan and to Japanese notions of aesthetics and beauty which are fundamentally different from western notions of beauty in art.

Unlike in the West, in Japan the concept of aesthetics is not seen as separate and divorced from daily life, but as an integral part of it. Japanese aesthetics has its roots in Shinto-Buddhism 神道 Shintō , with its emphasis on wholeness in nature and its celebration of nature and the landscape, as well as its emphasis on ethics, as well as Zen Buddhism 禪 and its philosophy. In Buddhism, everything is considered as either dissolving into ‘nothingness’ or the ‘void’ or evolving from it, whereby this void is, however, not a sort of ‘empty space’, but rather a space of potentiality from which things can grow and come into being and later return to it – everything is in transience and constant change.

Japanese concepts of aesthetics are based on the ancient ideals of wabi (transient and stark beauty), sabi (the beauty of aging and of natural patina) and Yūgen 幽玄 (subtlety and profound grace).

Wabi-sabi represents an aesthetic understanding based on the acceptance of transience and imperfection, an appreciation of the beauty of things which are imperfect, incomplete and impermanent. Things in decay or those in bud are evocative of wabi-sabi and are therefore appreciated. The concept of wabi-sabi is derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence (三法印 sanbōin ), which include impermanence (無常 mujō), emptiness or the absence of self (空 kū ) and suffering (苦 ku ). This notion of an aesthetic based on imperfection stands in direct contrast and opposition to the western understanding of beauty and aesthetics based on the ancient Greek ideal of perfection. Moreover, Japanese aesthetic ideals have an ethical connotation, since the aesthetic concepts are not only found in nature, but are also evocative of virtues of human character and appropriateness of behaviour. It is therefore believed that the appreciation and practice of art can instil virtue and civility in people.

The concept of wabi-sabi evolved from two different but related concepts, those of wabi and sabi, whose meanings overlapped and converged over time until they unified into the new combined concept of wabi-sabi (わび・さび or侘・寂). Wabi わび originally referred to the experience of loneliness of living in nature remote from the rest of society, whereas sabi (寂) means ‘withered’, ’lean’ or ‘chill’. There is an interesting phonological and etymological connection to the Japanese word sabi (錆), meaning ‘to rust’. While the two Kanji characters as well as their meanings are different ( ‘rust’, sabi), the original spoken word, which is pre-kanji or yamato-kotoba, is believed to be one and the same.

In Japanese aesthetics, wabi now connotes a quality of rustic simplicity, of understated elegance, quietness and freshness, and can be applied to both natural and human-made objects. Wabi can also refer to the imperfect quality of any object, due to limitations in design and quirks and anomalies arising from the process of manufacture and construction which add uniqueness to the object, in particular also with respect to unpredictable or changing conditions of usage. Sabi refers to the beauty or serenity that comes with age, and to the limited life-span of any object whose impermanence is evidenced in visible repairs and in its patina and wear.

Wabi-sabi has come to be defined as ‘flawed beauty’ and its characteristics include asymmetry, simplicity, irregularity, asperity or roughness, austerity, intimacy, modesty and economy, as well as an appreciation of the integrity of processes and of natural objects. The concept also has connotations of solitude and desolation.

Some examples illustrating the concept of wabi-sabi are chips or cracks in an item of pottery, which make the object more interesting and confer a greater meditative value onto it, the colour of glazed items which changes over time, as well as materials like wood, fabric and paper which exhibit visible changes over time, but also natural phenomena like falling autumn leaves.

A related design concept is the principle of miyabi ( 雅), which means ‘elegance’, ‘courtliness’ or ‘refinement’ and is sometimes translated as ‘heart-breaker’. It has its origins in the aristocratic ideals of the Heian era (平安時代 Heian jidai ), which prescribed the elimination of anything which was vulgar, unrefined, absurd, crude or rough and aimed for the polishing and refinement of manners and sentiments. Miyabi is closely connected to the notion of Mono-no-aware もののあわれ ( 物の哀れ, lit. ‘the pity of things’), a bittersweet awareness of the transience of things.

Wabi-sabi can be achieved through the seven aesthetic principles derived from Zen philosophy:

– Kanso (簡素) – simplicity; a clarity achieved through the omission of everything that is non-essential resulting in a plain, simple and natural manner

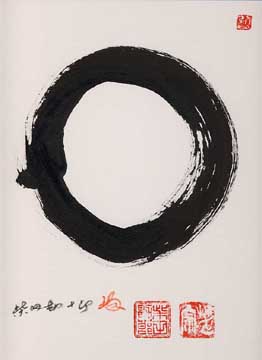

– Fukinsei (不均整) – asymmetry or irregularity; the notion of controlling balance in a composition via irregularity and asymmetry. An example for this principle is the Ensō (円相 circle) in brush painting (sumi-e 墨絵 or suibokuga 水墨画 ), also known as the Zen circle, which is often painted as an incomplete and unfinished circle, symbolizing the imperfection that is part of existence, as well as the absolute, the void, enlightenment, elegance and the universe itself. Some artists practice painting an ensō daily as a meditative spiritual Zen exercise. One of the aims of fukinsei is that by leaving an item incomplete, the beholder is given the opportunity to participate in the creative act by supplying the missing symmetry.

– Shizen (自然 , lit. ‘nature’) – naturalness; an absence of pretense or artificiality. An example for this principle is the Japanese garden日本庭園 nihon teien, whose intentional design based on naturally occurring rhythms and patterns, is, though ‘of nature’, also distinct from it.

– Yūgen (幽玄 , lit. ‘mystery’) – subtlety, profundity or suggestion; the term is derived from Chinese philosophical concepts and meant ‘dim’, ‘mysterious’ or ‘deep’ . Yūgen shows more by showing less and by limiting the information. The power of suggestion that visually implies more by not showing everything leaves things to the imagination, thereby enhancing their effect. Yūgen is the subtle profundity of things that is only vaguely suggested and is beyond what can be expressed in words, yet is of this world. Examples for yūgen are the subtle shades of bamboo on bamboo, to watch the sun set behind a mountain, to gaze after a ship that slowly disappears behind the horizon or to contemplate the flight of a flock of birds. Yūgen is a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of nature and the sad beauty of human suffering.

– Datsozoku (脱俗) – break or freedom from habit or routine, transcending the conventional. A feeling of surprise that arises from unexpected breaks in a pattern or a break from the ordinary. An interruptive break in a design.

– Seijaku (静寂) – tranquillity, stillness, solitude or an energized calm, in which one can find the essence of creative energy. An example for seijaku is meditation or the feeling one may have in a Japanese garden.

– Shibui (渋いadjective, lit.‘bitter tasting’)/shibumi (渋み noun) or shibusa (渋さ noun)– austerity, simple, subtle and unobtrusive beauty, beauty by understatement, elegant simplicity, minimalism. The term originally referred to a sour or astringent taste. Examples are objects which appear to be simple overall, but which include subtle details like textures, which balance simplicity with complexity, offering an appearance of which one does not tire but whose aesthetic value grows over time as one finds new meanings in its subtleties. Shibusa-objects circumscribe a fine line between contrasting aesthetic principles like restrained and spontaneous, or elegant and rough.

Another concept of Japanese aesthetics is the principle of iki ( いき, often written 粋), which has an etymological root meaning ‘pure’ or ‘unadulterated’ and a connotation of having an ‘appetite for life’, which is an expression of originality, simplicity, sophistication and spontaneity, and is emphemeral, straightforward, measured and unselfconscious. Iki can be expressed in the human appreciation of natural beauty or as a trait of human character or through artificial phenomena exhibiting human will or consciousness , but does not occur as such in nature. Iki is a broad term referring to qualities that are aesthetically pleasing, refinement with flair, or a tasteful manifestation of sensuality. The concept of iki is thought to have formed among the urban mercantile class (Chōnin 町人 townspeople) in Edo 江戸(lit. ‘bay entrance’ or ‘estuary’) in the Tokugawa period ((徳川時代 Tokugawa jidai 1603–1868).