Author: luc viatour, wikipedia commons

Today´s blog post will be about the names of the months in various Slavonic languages, which are not based on the Latin names and often have quite poetic names that have their origin in the seasonal changes and in agricultural activities typical for a specific time of the year. Many of these meanings are obvious, while others have been forgotten and their original meanings can only be guessed.

Here are the months in Ukrainian:

January січень – the slicing month (because of the ‘slicing’ cold)

February лютень – the angry month (angry frosts and blizzards)

March березень – the month of birches

April квітень – the month of flowers

May травень – the grass month

June червень – the red month (because fruits begin to ripen)

July липень – the month of linden trees

August серпень – the sickle month

September вересень – the heather month

October жовтень – the yellow month

November листопад – the month of falling leaves

December грудень – the month of the frozen soil

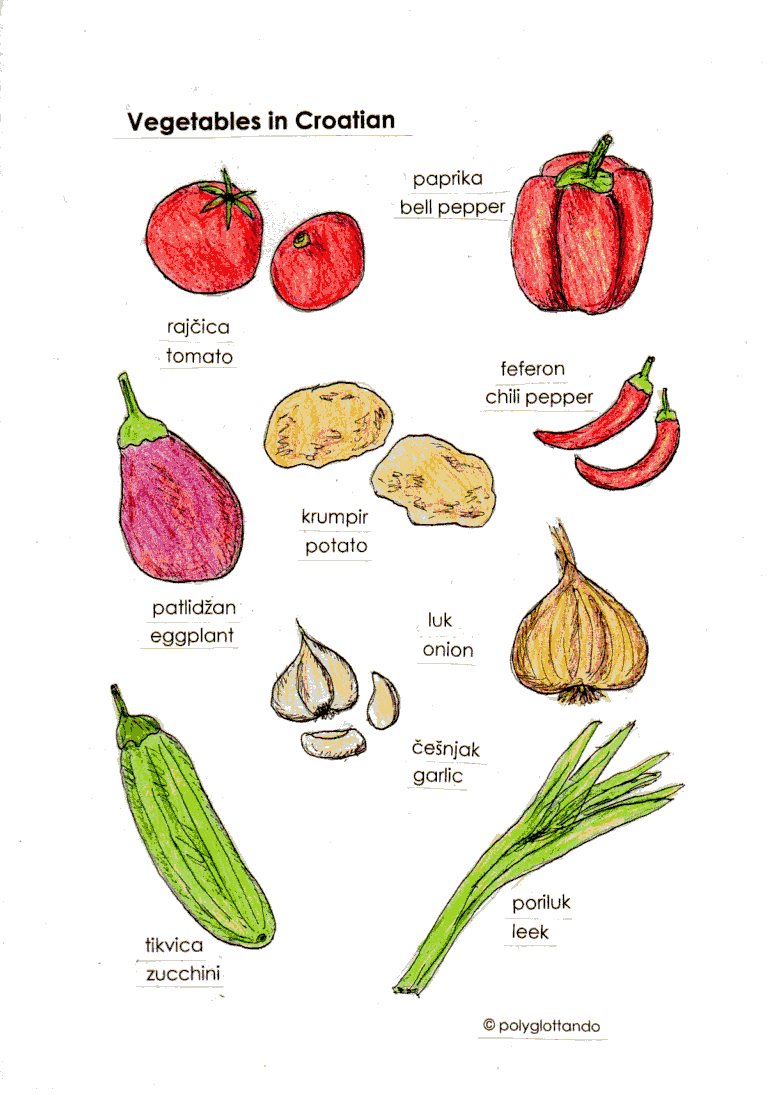

And here are the Croatian months:

January siječanj – the month of timber-cutting

February veljača – the huge month, with prolonged coldness

March ožujak

April travanj – the grass month

May svibanj – the month of vigorous growth and flowering shrubs

June lipanj – the month of linden blossoms

July srpanj – the month of the sickle (harvest month)

August kolovoz – the harvest month when wheat is harvested and threshed

September rujan – the reddish month (when the trees turn red)

October listopad – month of the falling leaves

November studeni – the cold month

December prosinac – the month when good weather and sunshine first appears after the autumn fogs

Author: Aplaster, wikipedia commons

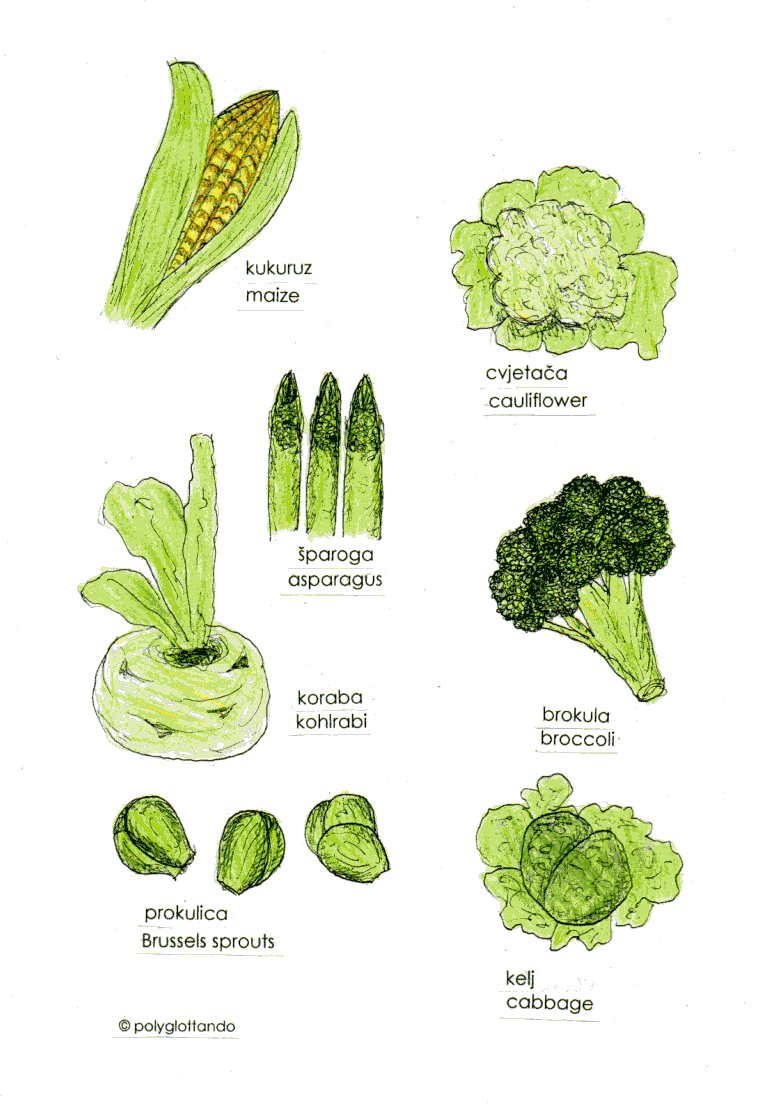

The Czech names for the months:

January leden – the month of ice

February únor – the month of renewal

March březen – the month of birches

April duben – the month of oaks

May květen – the blooming month

June červen – the red month (fruits are ripening)

July červenec – the red month where fruits are ripening

August srpen – the sickle month (harvest)

September září

October říjen – the rutting month (of deer)

November listopad – the month of falling leaves

December prosinec – the month when good weather appears after the autumn fogs

Author: poco a poco, wikipedia commons

And finally the months in Polish:

January styczeń

February luty – the month of angry frosts

March marzec

April kwiecień – the flowering and blooming month

May maj

June czerwiec – the red month when fruits are ripening

July lipiec – the month of linden trees

August sierpień – the month of the sickle (harvest)

September wrzesień – the heather month

October październik

November listopad – the month of falling leaves

December grudzień – the month where lumps form on roads and fields