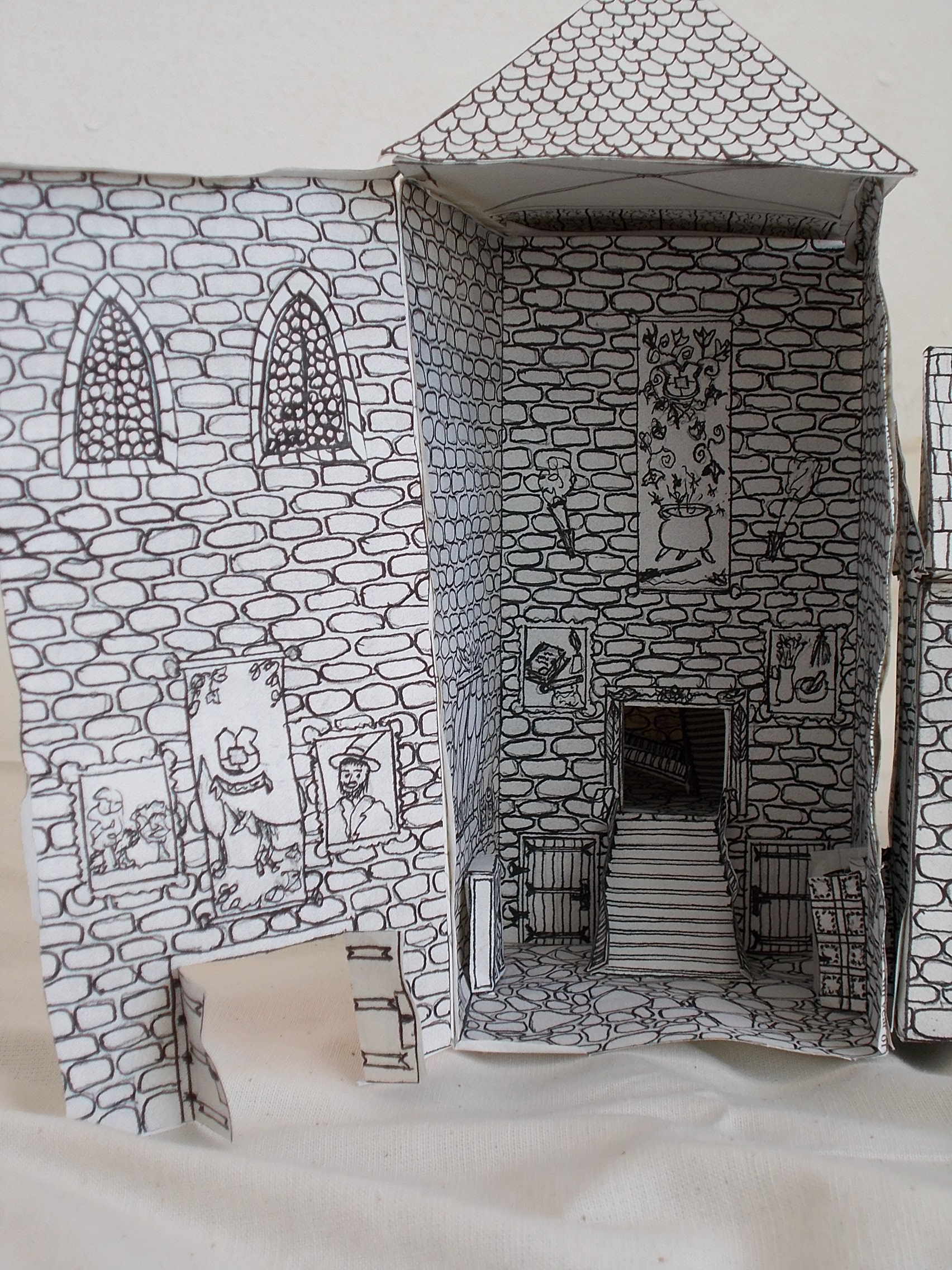

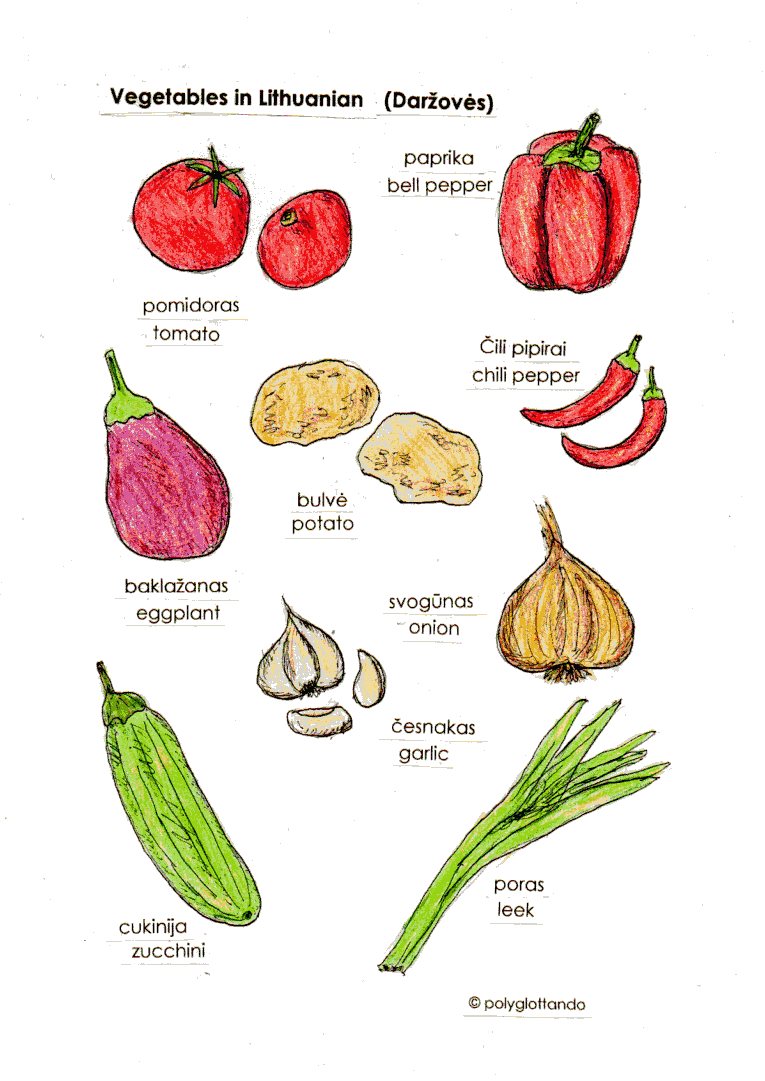

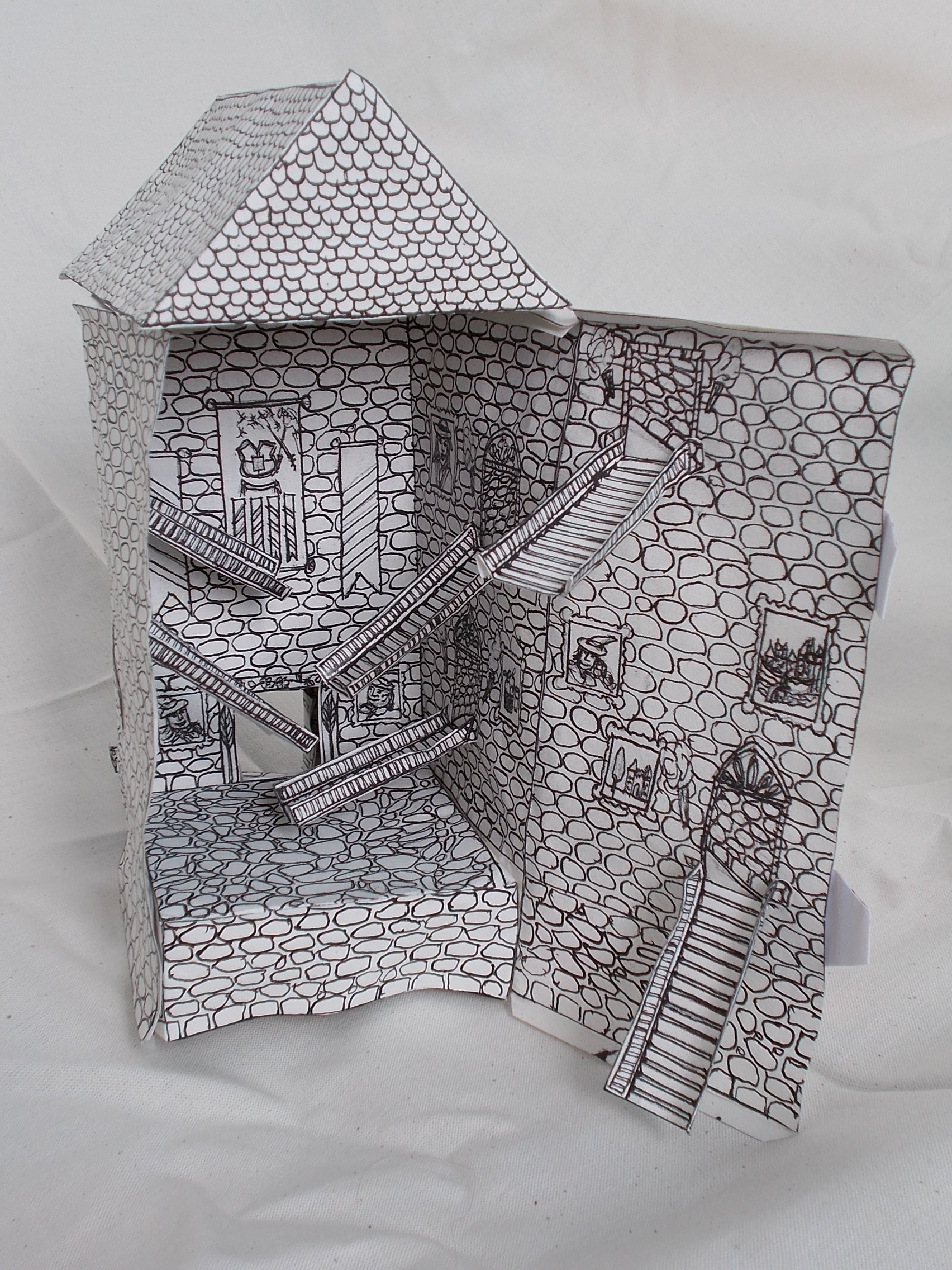

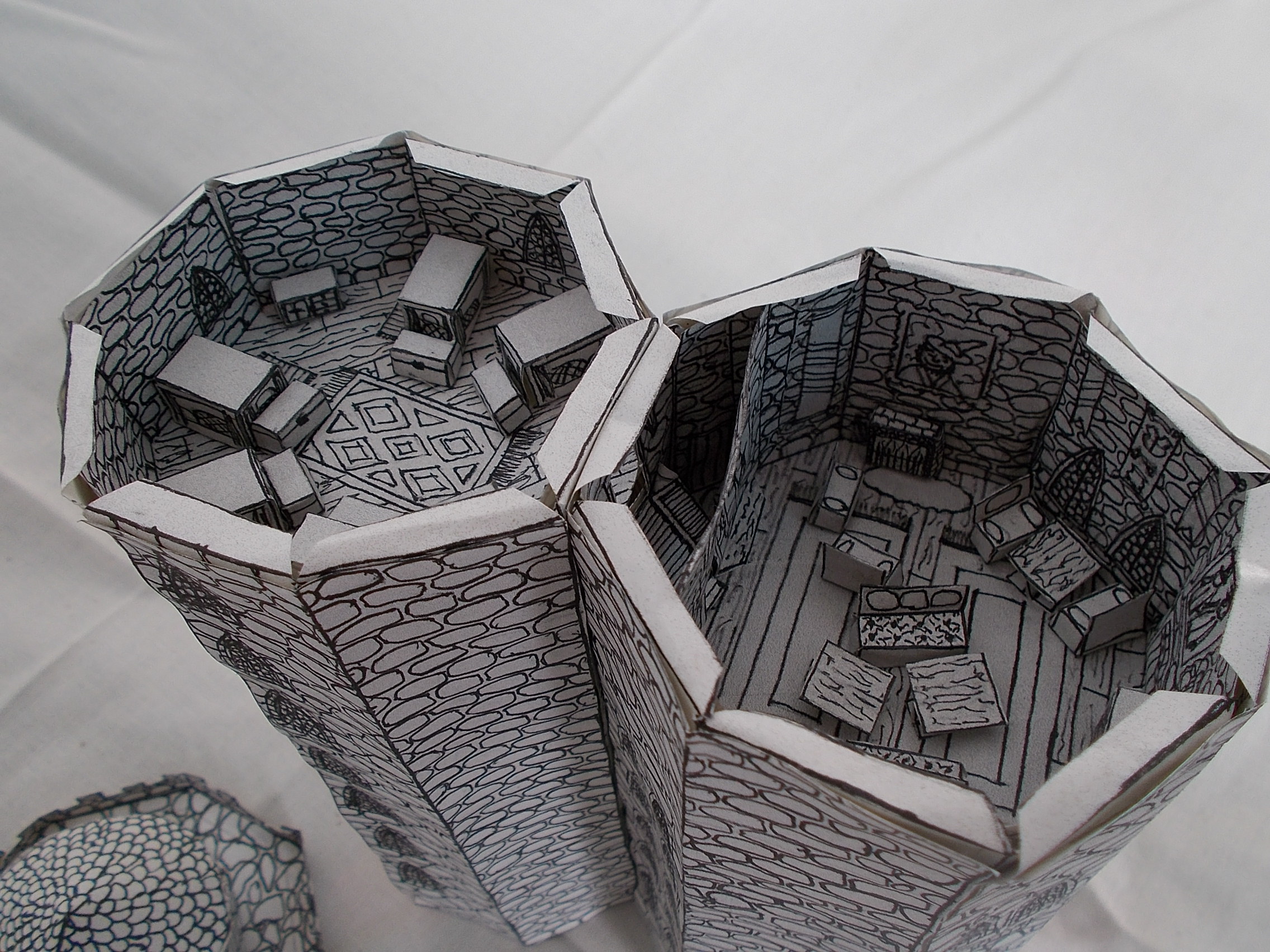

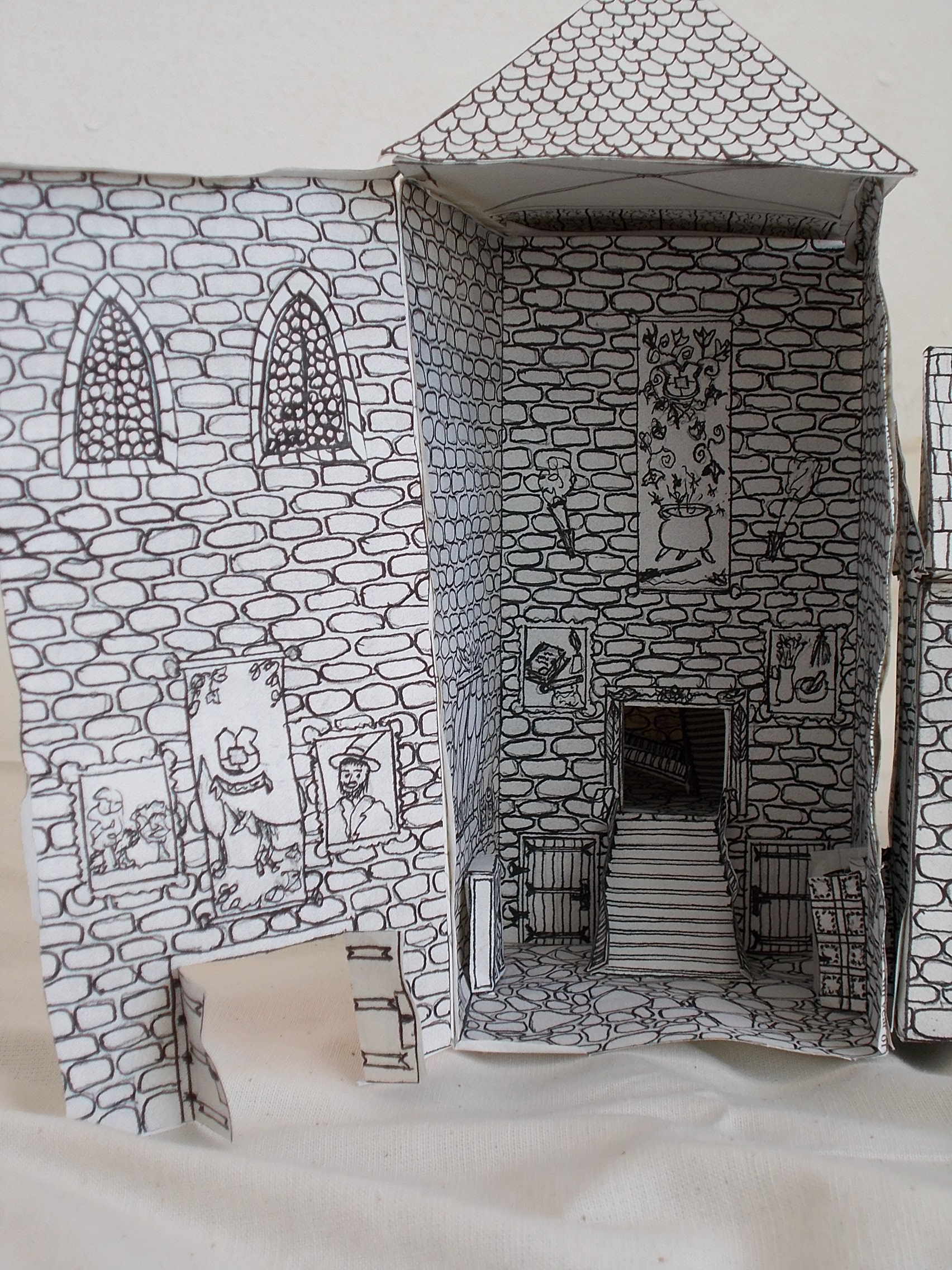

Author: Ecoturtleupcycling, used with permission

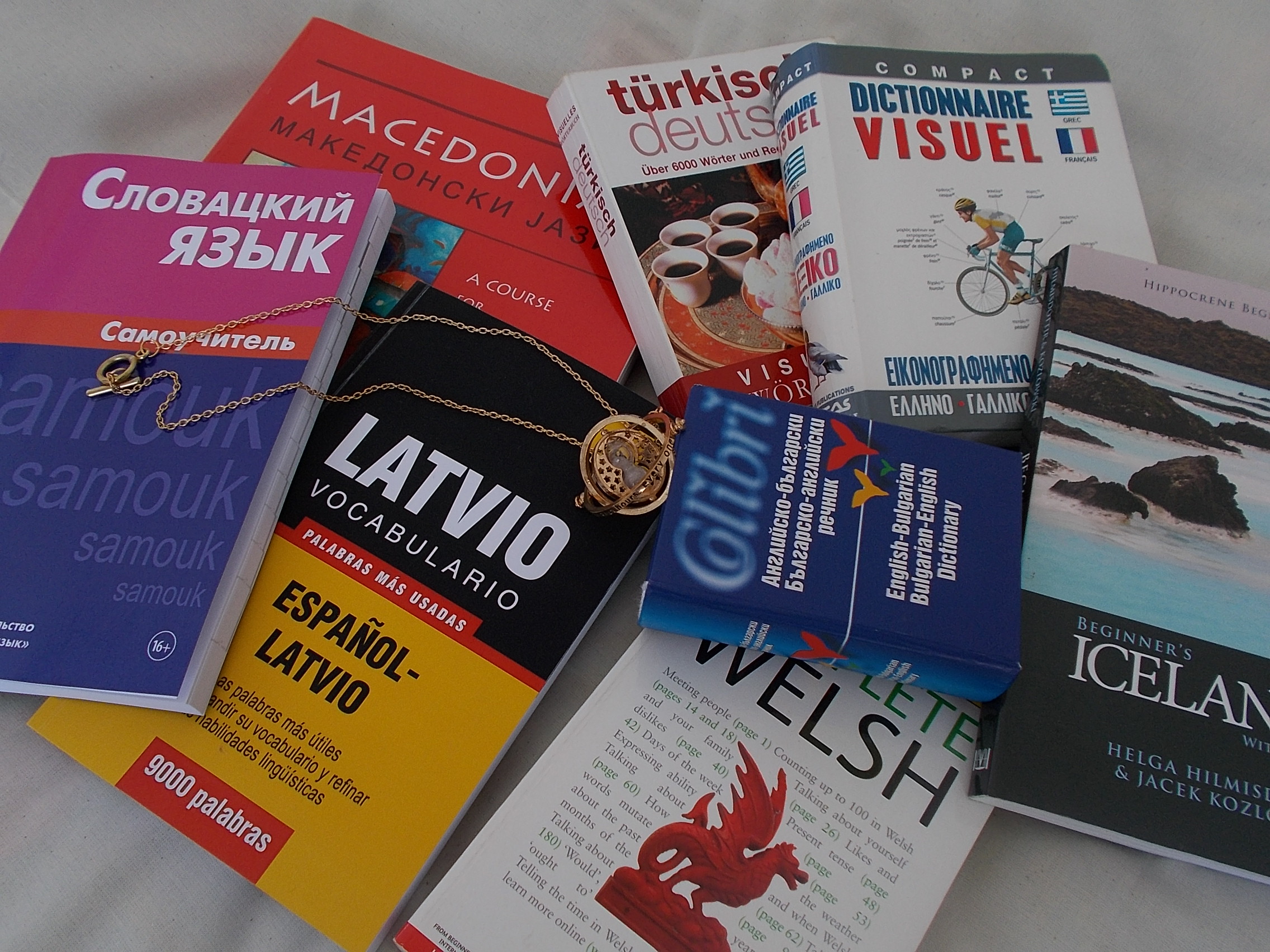

Today’s blog post is about the words of ‘Harry Potter’ in various languages and how the different characters and places in the books are called in translations of the books around the world. 🙂

French

Hogwarts castle is called Poudlard in French and Muggles are les Moldus. The 4 houses are: Gryffondor (Gryffindor), Serpentard (Slytherin), Poufsouffle (Hufflepuff), and Serdaigle (Ravenclaw). Severus Snape is called ‘Severus Rogue‘ and Draco Malfoy is ‘Drago Malefoy’. Hogwart’s caretaker Argus Filch is called Rusard and his cat Mrs Norris is ‘Miss Teigne‘. The Death Eaters are les Mangemorts and the Dementors are les Détraqueurs. Le Choixpeau magique is the Sorting Hat. House elves are les elfes de maison. The Whomping Willow is le saule cogneur.

Famous places: Le Chemin de Traverse (Diagon Alley), Le Chaudron Baveur (the Leaky Cauldron), la voie 9 3/4 (platform 9 3/4)

Afrikaans

Hogwarts is called Hogwarts Skool vir Heksery en Towerkuns, Hermione is called Hermien, Snape is Snerp, Dumbledore is Dompeldorius, the Burrow is die Konynenes, Quidditch is Kwiddiek and Diagon Alley is Diagonaalstraat. Moggels are Muggles and the 4 houses are: Griffindor, Hoesenproes (Hufflepuff), Rawenklou and Slibberin (Slytherin).

Author: Ecoturtleupcycling, used with permission

German

Hermione is called Hermine in the German version, Diagon Alley is Winkelgasse, the Death Eaters are die Todesser, the Pensieve is the Denkarium and the Burrow is der Fuchsbau and Honeydukes is der Honigtopf.

Dutch

In the Dutch version, most magic places and persons get a Dutch term that is different from the English original: thus, Hogwarts is called Zweinstein Hogeschool voor Hekserij en Hocus-Pocus and Harry’s friends are called Ron Wemel and Hermelien Griffel. Draco Malfoy is Draco Malfidus, Marcel Lubbermans is Neville Longbottom. The teachers: Albus Dumbledore is Albus Perkamentus, Professor McGonagall is Professor Anderling and Snape is Sneep. The Death Eaters are de Dooddoeners. Harry lives in Ligusterlaan nummer 4 with de Duffelingen (the Dursleys). Diagon Alley is de Wegisweg and the magic bank Gringotts is Goudgrijp. Muggels are Dreuzels. The 4 houses are Griffoendor, Zwadderich (Slytherin), Ravenklauw and Huffelpuf. Quidditch is Zwerkbal and the Sorting Hat is de sorteerhoed.

Author: Ecoturtleupcycling, used with permission

Italian

In the Italian translation, Harry goes to la Scuola di Magia e Stregoneria di Hogwarts where Albus Silente (Dumbledore) is the headmaster and where Severus Piton (Snape) and Miverva McGranitt (McGonagall) teach. Binario 9 e 3/4 is Platform 9 3/4 and il Paiolo Magico is the Leaky Cauldron and il Platano Picchiatore is the Whomping Willow.

I Babbani are the Muggles, i Mangiamorte the Death Eaters, i Dissenatori the Dementors and La Tana is the Burrow. Neville Paciock is Neville Longbottom, Horace Lumacorno is Horace Slughorn and Sibilla Cooman is Sibyll Trelawney (why she was given this pseudo-English name is a bit of a mystery though…?) . The 4 houses are: Tassorosso (Hufflepuff), Corvonero (Ravenclaw), Serpeverde (Slytherin) and Grifondoro (Gryffindor).

Author: Ecoturtleupcycling, photo used with permission

Czech

Also in the Czech version, just like in the Dutch translation, nearly all Hogwarts-related vocabulary gets a Czech term: Hogwarts is called Bradavice or with its full name Škola čar a kouzel v Bradavicích. The 4 houses are Nebelvír (Gryffindor), Mrzimor (Hufflepuff), Havraspár (Ravenclaw) a Zmijozel (Slytherin). Professor Dumbledore is called Albus Brumbál, Professor Gilderoy Lockhart is called Zlatoslav Lockhart, Professor Sprout is Professor Prýtová, Professor Flitwick is Filius Kratiknot and Professor Slughorn is Horácio Křiklan.

Author: Ecoturtleupcycling, photo used with permission

Spanish

Hogwarts is called Colegio Hogwarts de Magia y Hechicería and the Weasleys live in la Madriguera (the Burrow) and Diagon Alley is el Callejón Diagon. The Weasley twins work at Sortilegios Weasley (Weasleys Wizard Wheezes) and the Leaky Cauldron is el Caldero Chorreante. The Death Eaters are los Mortífagos, and Dobby is un elfo doméstico. The Marauders’ Map is el Mapa del Merodeador and the Sorting Hat is el Sombrero Seleccionador. Legilimency is known as legeremancia, a Pensieve is un pensadero and a Howler is una carta vociferadora.

Author: Ecoturtleupcycling, photo used with permission

Bulgarian

In the Bulgarian version, the Hogwarts-related terms largely keep their English names, and are only transliterated. So the 4 houses are: Грифиндор (Gryffindor), Слидерин (Slytherin) , Хафълпаф (Hufflepuff) and Рейвънклоу (Ravenclaw). Lord Voldemort is Лорд Волдемор. The Marauders Map is the Хитроумна карта, the Shrieking Shack is the Къща на крясъците and Honeydukes is Меденото царство.

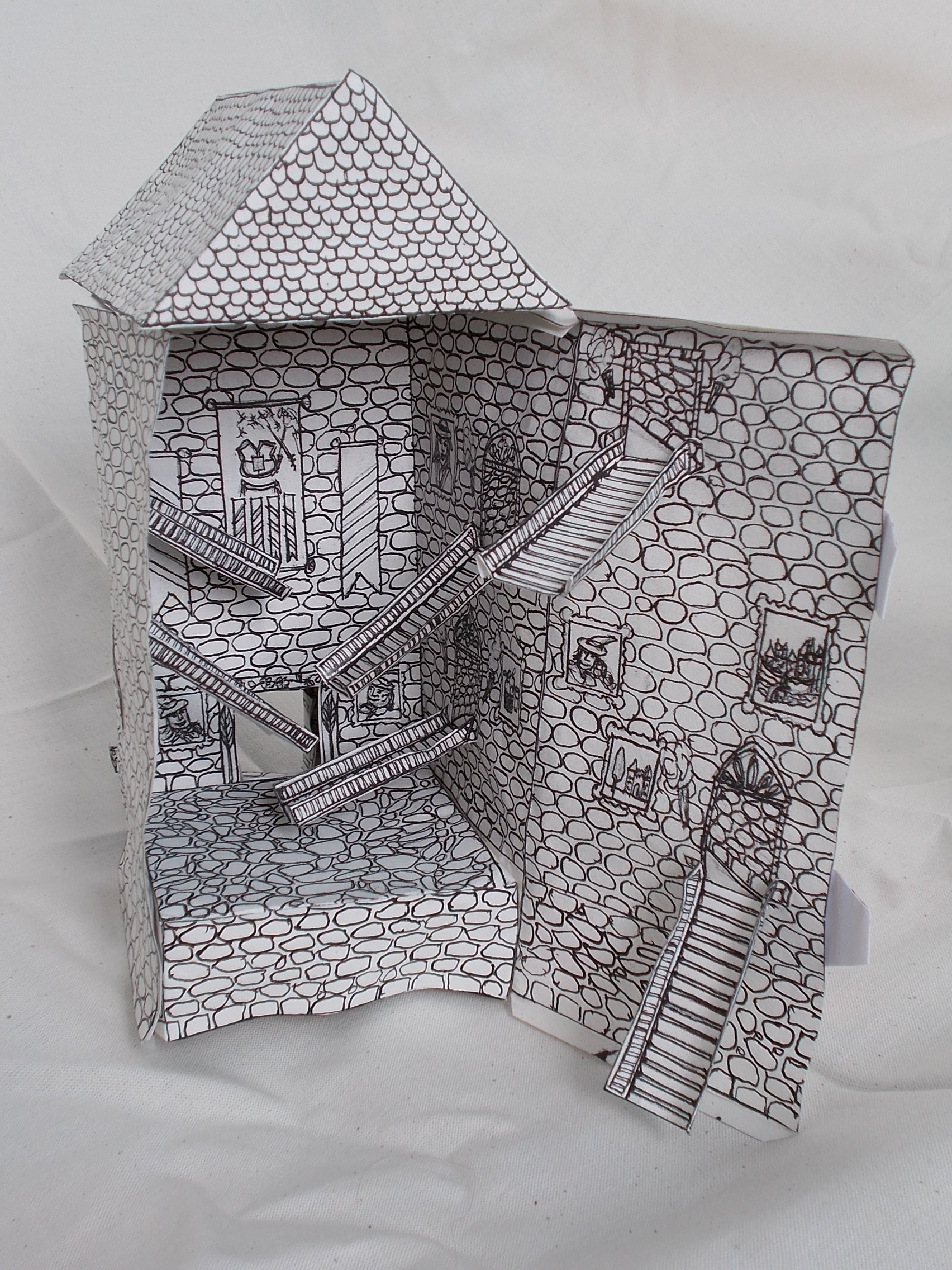

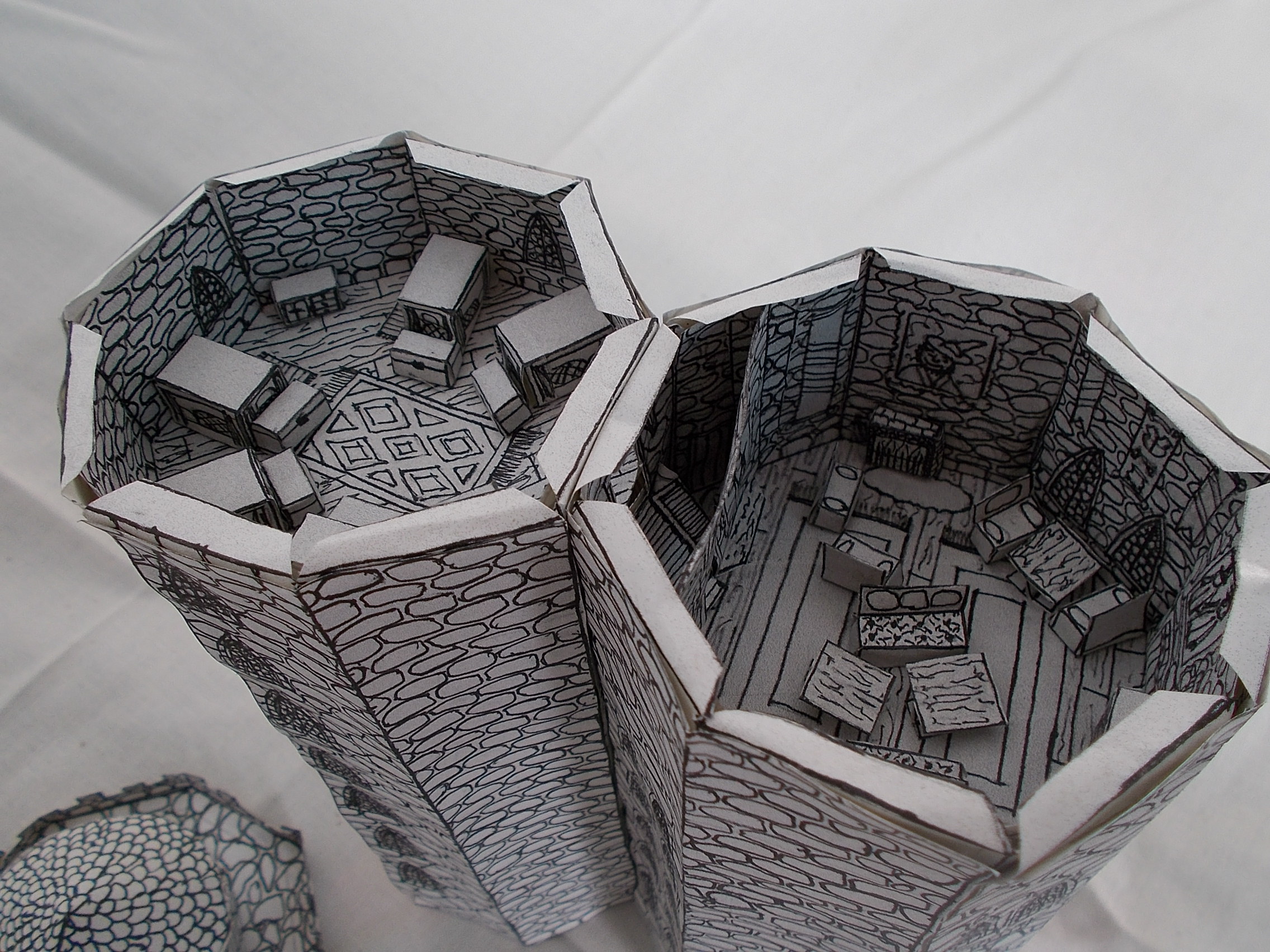

The great DIY paper castle in the photos is available from the friendly blog over at Ecoturtleupcycling https://www.etsy.com/shop/EcoTurtleUpcycling and permission to use the photos was granted.