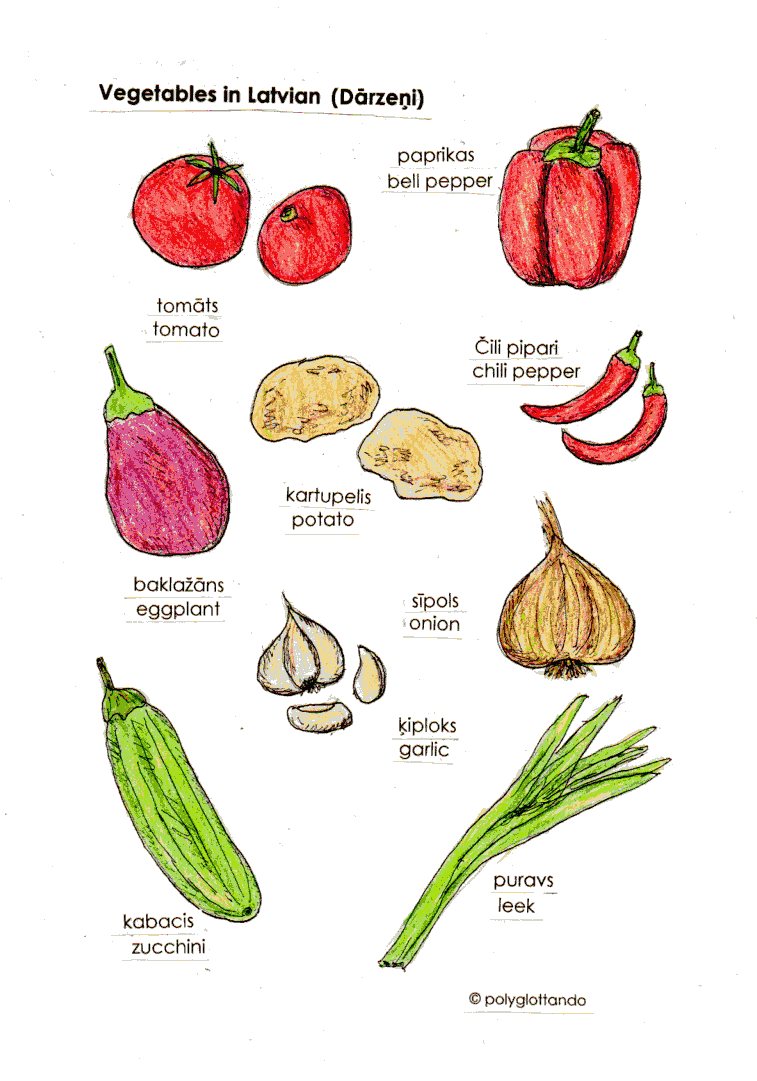

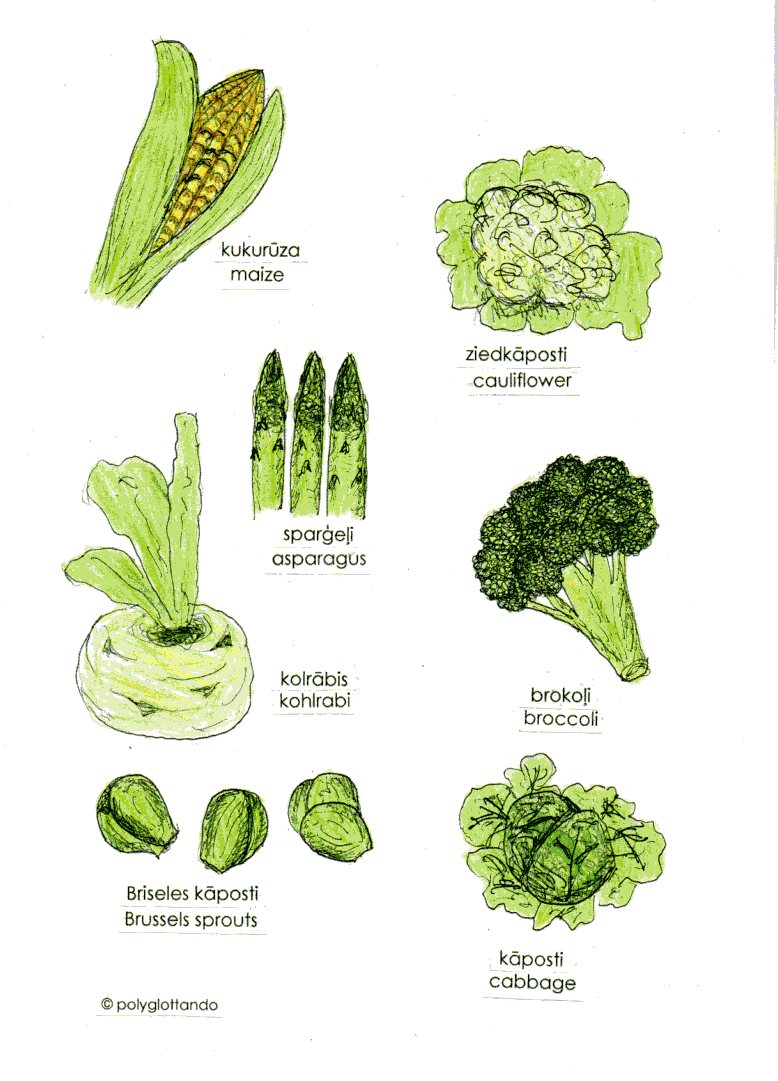

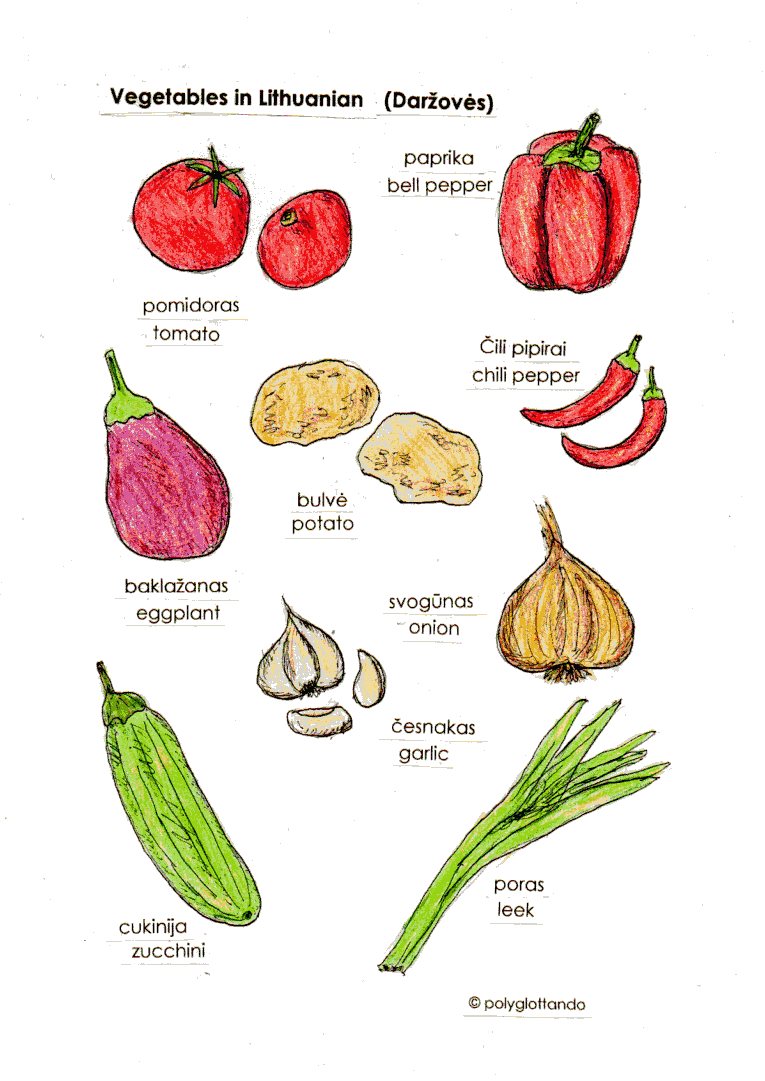

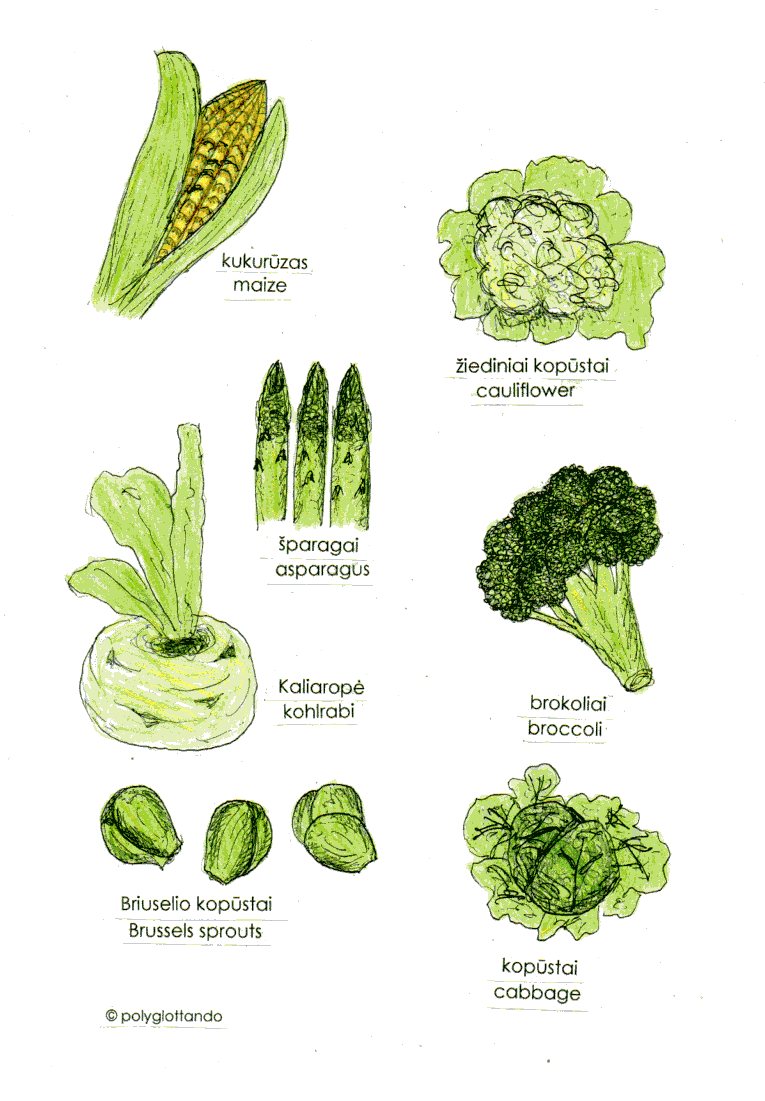

Today’s blog post is taking us to two Baltic countries and to their closely related languages, namely Latvian and Lithuanian, and the vocabulary for some vegetables.

Author Archives: polyglottando

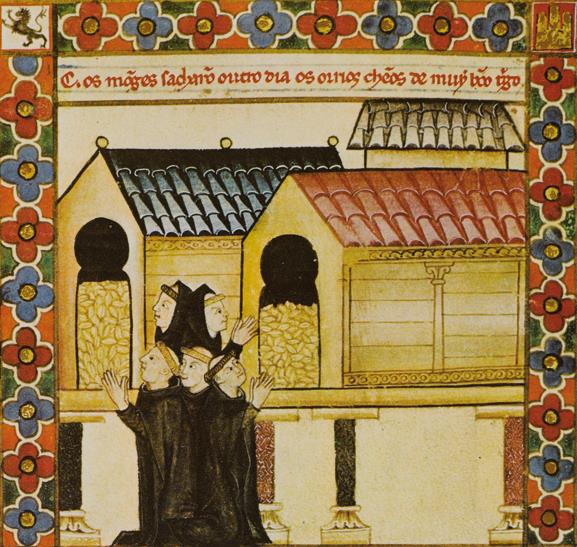

Focus on architecture: Hórreos (Galicia, Asturias, Northern Portugal, Basque Country)

Today’s blog post is taking us to the North of the Iberian Peninsula and to a type of building typical for that region: the hórreos. A hórreo is granary built on pillars which lift it above the ground to protect the stored grain and produce from water seepage. The pillars are topped by the so-called ‘staddle stones’ which prevent the access of rats and vermin. The oldest hórreos still in existence date from the 15th century. There are about 18,000 hórreos and paneras (hórreos with more than four pillars) in Asturias. There are several different types of hórreo, which vary according to the materials used for the pillars and decoration and the characteristics of the roof (thatched, tiled, slate, pitched or double pitched). Hórreos can be built in stone or made from wood and slits in the side walls allow ventilation.

Hórreos are known under different names, according to their region: In Galicia, they are called hórreo, paneira, canastro, piorno or cabazo, in Asturias hórreu or horru, in Basque they are called garea, garaia or garaixea and in Portugal espigueiro, canastro, caniço or hôrreo.

Also the staddle stones, which protect the grain from rodents, have different regional names: mueles or tornarratas in Asturian, zubiluzea in Basque and vira-ratos in Galician. The pillars are called pegollos in Asturian, esteos in Galician, and abearriak in Basque.

Welsh (Cymraeg): Some survival phrases and Welsh cakes

Today’s blog post will take us to the United Kingdom and more precisely to Wales Cymru and the Welsh language, which is called Cymraeg in Welsh. The word Cymru is derived from the Brythonic word combrogi, meaning “fellow-countrymen”. Welsh is a language of the Brittonic branch of the Celtic languages. Apart from being spoken in Wales and by people in England near the Welsh border, there is a Welsh colony in Chubut Province in Argentina, called Y Wladfa.

Here are a few survival phrases in Welsh:

Sut mae = hello

Hwyl = goodbye

Beth ydy’ch enw chi? = What’s your name?

.… ydw i = I am ….

Diolch yn fawr = thank you very much

diolch = thank you

croeso = you are welcome

Os gwelwch yn dda = please

Esgusodwch fi = excuse me

Mae’n ddrwg gyda fi = sorry

Iawn = OK

Dych chi’n siarad Cymraeg? = Do you speak Welsh?

Dw i ddim yn deall = I don’t understand

Welsh cakes picau ar y maen are a traditional dessert in Wales. They are baked on a bakestone (maen) or cast-iron griddle and are made from flour, fat, baking powder, sultanas, raisins, and/or currants, and may also contain spices such as cinnamon and nutmeg. They are round and usually measure about 7–8 cm (3 inches) in diameter and are 1–1.5 cm (0.5 inch) thick. Welsh cakes are served hot or cold dusted with caster sugar and are sometimes split and spread with jam.

An interesting article on the meaning of Welsh place names: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_toponymy

How to boost your fluency by learning vocabulary more effectively

Today’s blog post is about some tips and tricks to learn vocabulary more effectively to boost your fluency in your target language. While there is no shortcut to learning your vocabulary, there are some ways how you can make your learning more organized and effective to yield better results.

1. Instead of just learning words individually, learn them also as collocations (a collocation is a combination of words that frequently occur together, e.g. ‘to read a book’, ‘to go by train’, etc.). This is especially useful for languages which are governed by cases, like Russian, Polish or German, because when you memorize collocations, you won’t always have to think about the correct declination or case the words must be in in frequent expressions. Knowing frequent collocations by heart will therefore boost your fluency when speaking or writing your target language.

2. Learn frequent phrases and expressions by heart from a phrasebook. While a phrasebook alone will never suffice to learn a complete language, learning frequent phrases or ‘building blocks’ of expressions by heart is a good way to develop some conversational fluency especially at the beginning when you start learning a new language.

3. Use thematic vocabulary lists to learn words around a given topic. This is very useful when you want to speak or write about a given topic or theme, e.g. a hobby, because a good list will teach you not only expressions that you are likely to need in this context and words which are likely to occur together and which you will encounter, but also synonyms and antonyms for this context, collocations or groups of related words based on a word stem, and useful verbs, adjectives and nouns to talk about the topic of your choice.

4. Subscribe to a Word of the Day for your target language(s). While this will not help you directly to be able to speak about a topic, a ‘Word of the Day’-subscription is nevertheless highly useful both for regular repetition of random words and for seeing and hearing the words used in the context of a sentence which will help you gain more fluency in the long term. Since fluency depends on being instinctively familiar with words that occur and are expected in a certain context and situation, the more often you see and hear and come across words, the more familiar you will be with them and the more easily they will pop into your mind when you need them in a conversation or when writing a text. The ‘Word of the Day’-function is therefore not only an excellent means for repetition but also to keep up the languages you already speak.

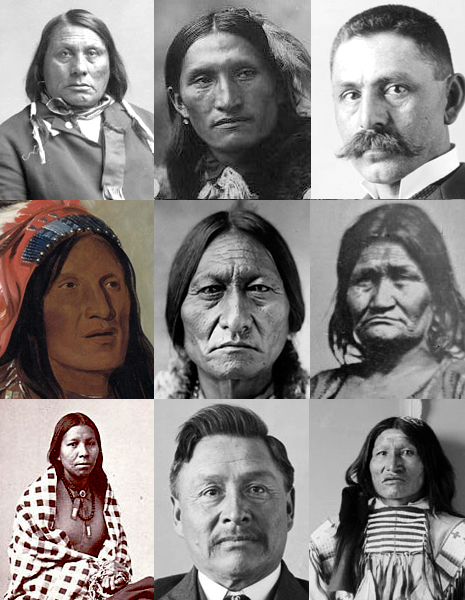

The names of the months in Lakota (Lakhotiyapi) and the Ojibwe legend of the origin of the dreamcatcher

Author: John C.H. Grabill, digital restoration by Michel Vuijlsteke via Wikipedia Commons

Oglala girl in front of a tipi

Today’s blog post will take us to two First Nations in the US and Canada, and will be about the names of the months in Lakota or Lakȟótiyapi (also known as Sioux), a Siouan language spoken by the Lakota nation (Lakȟóta) in North and South Dakota in the United States, and tell the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) legend of the origin of the dreamcatcher.

The Lakȟótiyapi word ‘wi’ means ‘moon’ or ‘month’, and ‘wiyawapi’ means ‘a months count or calendar’.

January wiocokanyan (lit. ‘the middle moon’) or wiotehika (‘the hard moon’)

February cannapopa wi (‘the moon when trees crack because of the cold’) or tiyoheyunka wi (‘moon where the frost is settling on the inside wall of the house or tent’) or wicata wi (‘the raccoon moon’)

March ištawicayazan wi (‘the moon of prevailing sore eyes’) or ištawicaniyan wi (‘the moon of sore eyes’) or šiyo ištohcapi wi (šiyo ‘grouse, prairie hen’; ‘moon of the grouse and of sore eyes’)

April wihakakta cèpapi (‘wihakakta’ means ‘the fifth child’, so called because it was usually the last child or the youngest; ‘cepa’ means fat; the youngest wife had to crack the bones and people would get fat on the marrow)

May canwapto wi (‘moon in which the leaves are green’ from ‘canwape’ [from can ‘tree’ + ape ‘leaf’] meaning ‘leaves’ or ‘small branches’) or wójupi wi (‘the moon of planting’)

June tínpsinla itkahca wi (‘the moon when the seedpods of the wild turnip blossom’) or wípazuka wašte (‘wípazukan’, a red berry growing in small bunches in June; ‘wašte’ meaning ‘good, pretty’; therefore ‘moon of the good red wípazukan berries’)

July canpasapa wi (‘the moon when the choke-cherries are black’) or wiocokanyan (‘the middle moon’)

August wasuton wi (‘the harvest moon’)

September canwape gi wi (‘moon in which leaves turn brown’)

October canwape kasna wi (‘the moon in which the wind shakes off leaves’)

November takiyuha (‘the moon when deer copulate’) or waniyetu wi (‘the winter moon’)

December tahecapšun wi (‘the moon in which deer shed their horns) or wanicokan wi (‘the mid-winter moon’)

What is quite interesting is that the word ‘wiocokanyan’, meaning the ‘middle moon’, can refer to both January and July.

And some Lakhotiya words:

Tatanka the male buffalo

Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka – lit. ‘the sacred’ or ‘the divine’, usually translated as ‘the Great Mystery’; the term refers to the power or sacredness that resides in everything, resembling pantheistic or animistic beliefs. Every creature and object has some aspects that are considered wakȟáŋ (“holy”).

iháŋbla gmunka (iháŋbla ‘to dream, to have visions’, gmunka ‘to trap’) ‘dreamcatcher’, a handmade object made from a willow hoop and sinew or cordage made from plants, which is woven around the hoop to form a net or web. The dreamcatcher is decorated with sacred items such as beads and feathers which all have a symbolic meaning. Dreamcatchers actually have their origins in the Ojibwe nation, where they are called bawaajige nagwaagan meaning “dream snare” or asabikeshiinh (the inanimate form of the word for ‘spider’), but have been adopted by Native Americans of different nations in the Pan-Indian Movement of the 1960’s and 70’s as a symbol of unity and identification with the First Nations. However, other groups see dreamcatchers as offensively misappropriated and misused by non-Natives. The circular shape represents how giizis (Ojibwe, meaning ‘the sun, moon, month’) travels each day across the sky.

There is an ancient Ojibwe legend about the origin of the dreamcatcher: the Spider Woman, known as Asibikaashi, took care of the children and the people on the land. Eventually, when the Ojibwe Nation spread all over North America, it became difficult for Asibikaashi to reach all the children. So the mothers and grandmothers would weave magical webs for the children from willow hoops in the form of dreamcatchers which would filter out all bad dreams and only allow good thoughts to enter the mind, making the bad dreams disappear once the sun rises.

Finally a booktip for those of you who are interested in Native American spirituality and culture in general and the Lakota Nation in particular:

‘The Lakota Way – Stories and Lessons for Living’ by Joseph M. Marshall III

If you live in the UK: http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0142196096

If you live in the US: http://amzn.com/0142196096

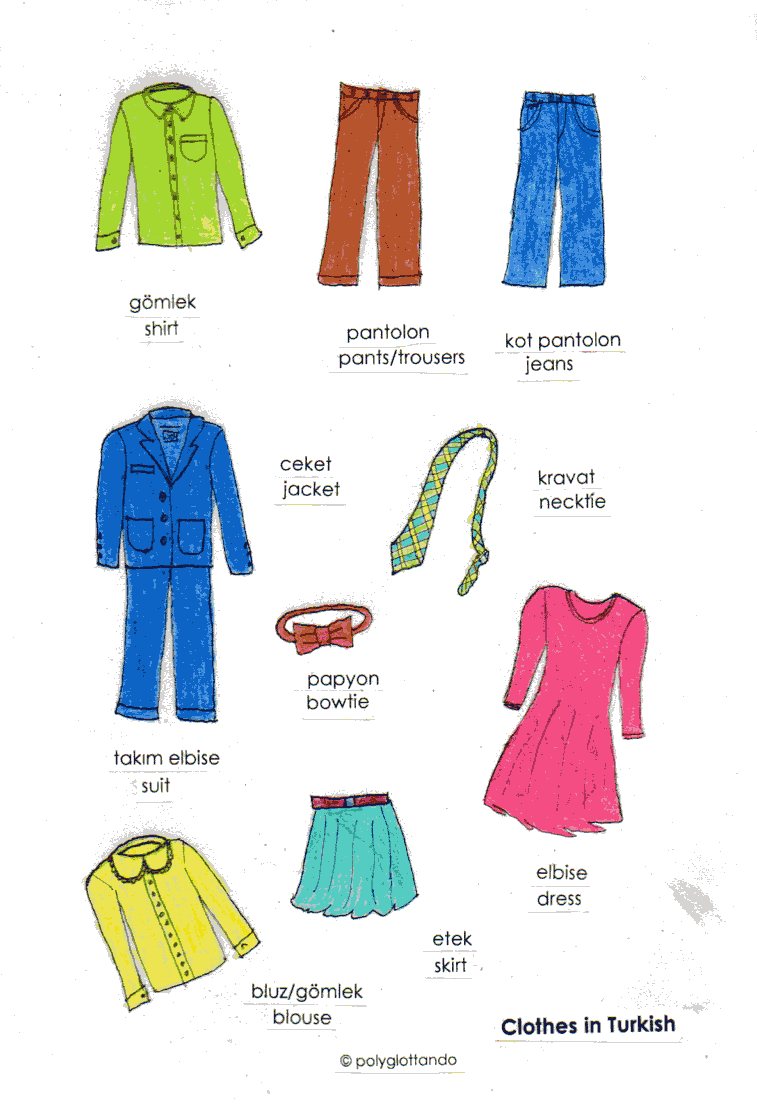

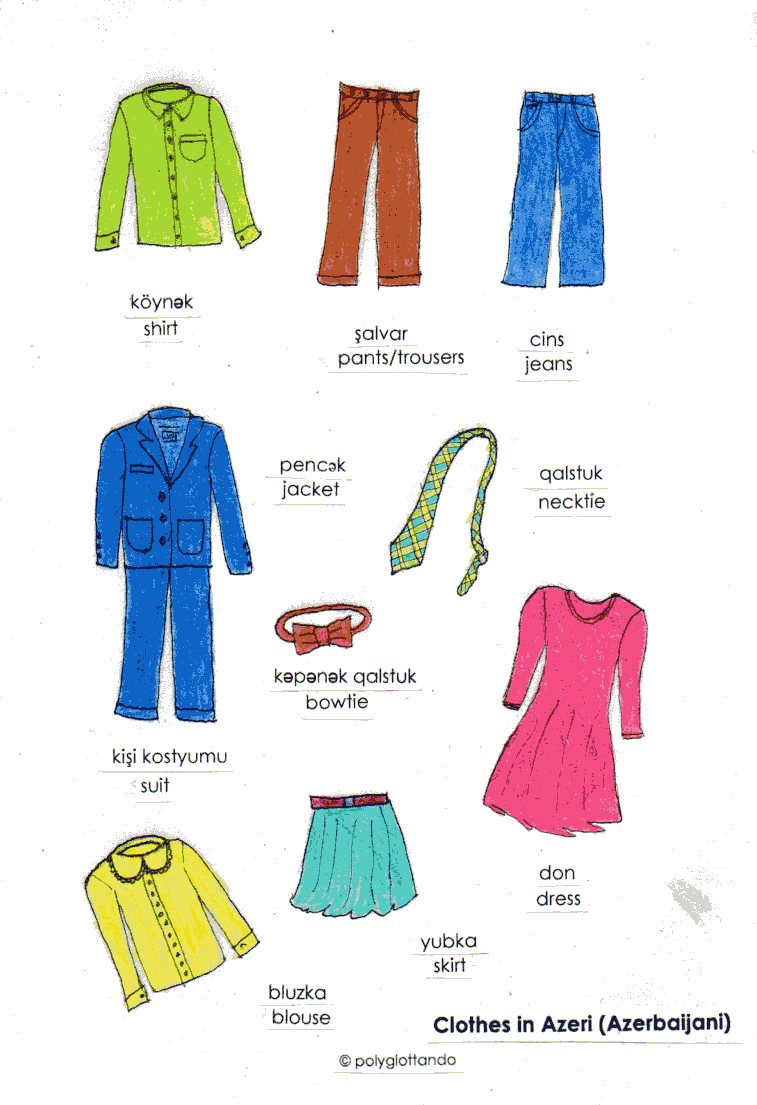

Vocabulary: Clothes in Turkish and Azeri (Azerbaijani)

Focus on art: Japanese aesthetics and design principles

Today’s blog post is taking us to Japan and to Japanese notions of aesthetics and beauty which are fundamentally different from western notions of beauty in art.

Unlike in the West, in Japan the concept of aesthetics is not seen as separate and divorced from daily life, but as an integral part of it. Japanese aesthetics has its roots in Shinto-Buddhism 神道 Shintō , with its emphasis on wholeness in nature and its celebration of nature and the landscape, as well as its emphasis on ethics, as well as Zen Buddhism 禪 and its philosophy. In Buddhism, everything is considered as either dissolving into ‘nothingness’ or the ‘void’ or evolving from it, whereby this void is, however, not a sort of ‘empty space’, but rather a space of potentiality from which things can grow and come into being and later return to it – everything is in transience and constant change.

Japanese concepts of aesthetics are based on the ancient ideals of wabi (transient and stark beauty), sabi (the beauty of aging and of natural patina) and Yūgen 幽玄 (subtlety and profound grace).

Wabi-sabi represents an aesthetic understanding based on the acceptance of transience and imperfection, an appreciation of the beauty of things which are imperfect, incomplete and impermanent. Things in decay or those in bud are evocative of wabi-sabi and are therefore appreciated. The concept of wabi-sabi is derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence (三法印 sanbōin ), which include impermanence (無常 mujō), emptiness or the absence of self (空 kū ) and suffering (苦 ku ). This notion of an aesthetic based on imperfection stands in direct contrast and opposition to the western understanding of beauty and aesthetics based on the ancient Greek ideal of perfection. Moreover, Japanese aesthetic ideals have an ethical connotation, since the aesthetic concepts are not only found in nature, but are also evocative of virtues of human character and appropriateness of behaviour. It is therefore believed that the appreciation and practice of art can instil virtue and civility in people.

The concept of wabi-sabi evolved from two different but related concepts, those of wabi and sabi, whose meanings overlapped and converged over time until they unified into the new combined concept of wabi-sabi (わび・さび or侘・寂). Wabi わび originally referred to the experience of loneliness of living in nature remote from the rest of society, whereas sabi (寂) means ‘withered’, ’lean’ or ‘chill’. There is an interesting phonological and etymological connection to the Japanese word sabi (錆), meaning ‘to rust’. While the two Kanji characters as well as their meanings are different ( ‘rust’, sabi), the original spoken word, which is pre-kanji or yamato-kotoba, is believed to be one and the same.

In Japanese aesthetics, wabi now connotes a quality of rustic simplicity, of understated elegance, quietness and freshness, and can be applied to both natural and human-made objects. Wabi can also refer to the imperfect quality of any object, due to limitations in design and quirks and anomalies arising from the process of manufacture and construction which add uniqueness to the object, in particular also with respect to unpredictable or changing conditions of usage. Sabi refers to the beauty or serenity that comes with age, and to the limited life-span of any object whose impermanence is evidenced in visible repairs and in its patina and wear.

Wabi-sabi has come to be defined as ‘flawed beauty’ and its characteristics include asymmetry, simplicity, irregularity, asperity or roughness, austerity, intimacy, modesty and economy, as well as an appreciation of the integrity of processes and of natural objects. The concept also has connotations of solitude and desolation.

Some examples illustrating the concept of wabi-sabi are chips or cracks in an item of pottery, which make the object more interesting and confer a greater meditative value onto it, the colour of glazed items which changes over time, as well as materials like wood, fabric and paper which exhibit visible changes over time, but also natural phenomena like falling autumn leaves.

A related design concept is the principle of miyabi ( 雅), which means ‘elegance’, ‘courtliness’ or ‘refinement’ and is sometimes translated as ‘heart-breaker’. It has its origins in the aristocratic ideals of the Heian era (平安時代 Heian jidai ), which prescribed the elimination of anything which was vulgar, unrefined, absurd, crude or rough and aimed for the polishing and refinement of manners and sentiments. Miyabi is closely connected to the notion of Mono-no-aware もののあわれ ( 物の哀れ, lit. ‘the pity of things’), a bittersweet awareness of the transience of things.

Wabi-sabi can be achieved through the seven aesthetic principles derived from Zen philosophy:

– Kanso (簡素) – simplicity; a clarity achieved through the omission of everything that is non-essential resulting in a plain, simple and natural manner

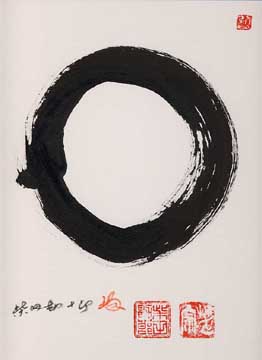

– Fukinsei (不均整) – asymmetry or irregularity; the notion of controlling balance in a composition via irregularity and asymmetry. An example for this principle is the Ensō (円相 circle) in brush painting (sumi-e 墨絵 or suibokuga 水墨画 ), also known as the Zen circle, which is often painted as an incomplete and unfinished circle, symbolizing the imperfection that is part of existence, as well as the absolute, the void, enlightenment, elegance and the universe itself. Some artists practice painting an ensō daily as a meditative spiritual Zen exercise. One of the aims of fukinsei is that by leaving an item incomplete, the beholder is given the opportunity to participate in the creative act by supplying the missing symmetry.

– Shizen (自然 , lit. ‘nature’) – naturalness; an absence of pretense or artificiality. An example for this principle is the Japanese garden日本庭園 nihon teien, whose intentional design based on naturally occurring rhythms and patterns, is, though ‘of nature’, also distinct from it.

– Yūgen (幽玄 , lit. ‘mystery’) – subtlety, profundity or suggestion; the term is derived from Chinese philosophical concepts and meant ‘dim’, ‘mysterious’ or ‘deep’ . Yūgen shows more by showing less and by limiting the information. The power of suggestion that visually implies more by not showing everything leaves things to the imagination, thereby enhancing their effect. Yūgen is the subtle profundity of things that is only vaguely suggested and is beyond what can be expressed in words, yet is of this world. Examples for yūgen are the subtle shades of bamboo on bamboo, to watch the sun set behind a mountain, to gaze after a ship that slowly disappears behind the horizon or to contemplate the flight of a flock of birds. Yūgen is a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of nature and the sad beauty of human suffering.

– Datsozoku (脱俗) – break or freedom from habit or routine, transcending the conventional. A feeling of surprise that arises from unexpected breaks in a pattern or a break from the ordinary. An interruptive break in a design.

– Seijaku (静寂) – tranquillity, stillness, solitude or an energized calm, in which one can find the essence of creative energy. An example for seijaku is meditation or the feeling one may have in a Japanese garden.

– Shibui (渋いadjective, lit.‘bitter tasting’)/shibumi (渋み noun) or shibusa (渋さ noun)– austerity, simple, subtle and unobtrusive beauty, beauty by understatement, elegant simplicity, minimalism. The term originally referred to a sour or astringent taste. Examples are objects which appear to be simple overall, but which include subtle details like textures, which balance simplicity with complexity, offering an appearance of which one does not tire but whose aesthetic value grows over time as one finds new meanings in its subtleties. Shibusa-objects circumscribe a fine line between contrasting aesthetic principles like restrained and spontaneous, or elegant and rough.

Another concept of Japanese aesthetics is the principle of iki ( いき, often written 粋), which has an etymological root meaning ‘pure’ or ‘unadulterated’ and a connotation of having an ‘appetite for life’, which is an expression of originality, simplicity, sophistication and spontaneity, and is emphemeral, straightforward, measured and unselfconscious. Iki can be expressed in the human appreciation of natural beauty or as a trait of human character or through artificial phenomena exhibiting human will or consciousness , but does not occur as such in nature. Iki is a broad term referring to qualities that are aesthetically pleasing, refinement with flair, or a tasteful manifestation of sensuality. The concept of iki is thought to have formed among the urban mercantile class (Chōnin 町人 townspeople) in Edo 江戸(lit. ‘bay entrance’ or ‘estuary’) in the Tokugawa period ((徳川時代 Tokugawa jidai 1603–1868).

Balinese: language and mythology (the world turtle Bedawang)

Today’s blog post is taking us to South East Asia, to the Indonesian island of Bali and its language, Basa Bali. Balinese is an Austronesian language, like Indonesian, and is spoken by about 3 million people on the island of Bali and in parts of Indonesia like western Lombok and some villages in Sulawesi, where many Balinese anak Bali live. Virtually all people in Bali also speak Bahasa Indonesia, the national language, except for some old people. While the grammatical structures of Indonesian and Balinese are quite similar, the vocabulary of both languages is quite different. Balinese has many words of Sanskrit, Farsi, Tamil as well as Javanese, Dutch and Portuguese origin, reflecting the Hindu background of Balinese society. A particularity of Balinese is its two levels of social distinction, which each has its own set of parallel vocabulary and which reflect both the social status of the speaker as well as that of the person addressed. Biasa or common words are used by people of equal social status and they reflect informality and intimacy among the speakers. In contrast, halus or refined words reflect formality and distance among the speakers. There are, however, only a certain number of words that are different in both language levels, mainly those concerning human beings, while most words can be used for both levels. Topics that are considered very halus, like religion, always require the use of halus words. The Balinese are predominantly Hindus and the traditional Balinese social structure is therefore based on the Hindu caste system. However, ‘caste’ in Bali is not at all based on rigid distinctions and restrictions of occupations as in India, it merely reflects a notion of general social status, which in turn is reflected in the language. The 4 castes are:

Today’s blog post is taking us to South East Asia, to the Indonesian island of Bali and its language, Basa Bali. Balinese is an Austronesian language, like Indonesian, and is spoken by about 3 million people on the island of Bali and in parts of Indonesia like western Lombok and some villages in Sulawesi, where many Balinese anak Bali live. Virtually all people in Bali also speak Bahasa Indonesia, the national language, except for some old people. While the grammatical structures of Indonesian and Balinese are quite similar, the vocabulary of both languages is quite different. Balinese has many words of Sanskrit, Farsi, Tamil as well as Javanese, Dutch and Portuguese origin, reflecting the Hindu background of Balinese society. A particularity of Balinese is its two levels of social distinction, which each has its own set of parallel vocabulary and which reflect both the social status of the speaker as well as that of the person addressed. Biasa or common words are used by people of equal social status and they reflect informality and intimacy among the speakers. In contrast, halus or refined words reflect formality and distance among the speakers. There are, however, only a certain number of words that are different in both language levels, mainly those concerning human beings, while most words can be used for both levels. Topics that are considered very halus, like religion, always require the use of halus words. The Balinese are predominantly Hindus and the traditional Balinese social structure is therefore based on the Hindu caste system. However, ‘caste’ in Bali is not at all based on rigid distinctions and restrictions of occupations as in India, it merely reflects a notion of general social status, which in turn is reflected in the language. The 4 castes are:

Brahmana , the highest caste and those of priests (Brahmin in India), the name of members of this caste starts with Ida Bagus (m) or Ida Ayu (f);

ksatria the second caste and ruler and warrior caste (Kshatriya in India), the name of members of this caste starts with Anak Agung or Cokorda/Tjokorde Gde (m) or Tjokorde Istri (f);

wesia the third caste and that of merchants and officials (weysha in India), the name of members of this caste starts with I Gusti ;

and the sudra or rice farmers’ caste (shudra in India, the non-caste). Only about 7 % of the anak Bali belong to the triwangsa or the three higher castes, while the large majority, more than 90%, belong to the sudra caste.

Generally, people of a lower caste will ‘speak upward’ to a member of a higher caste, i.e. they will choose the more refined halus words. Likewise, a member of a higher caste will ‘speak down’ to a member of a lower class, that is, choose the common biasa words. So a farmer speaking to another farmer would use biasa words, and a member of a high caste speaking with another high class individual would use halus words. However, a farmer speaking with or referring to a member of the high class would use halus words.

Here is an example:

Biasa level: Dadi tawang adane? May I know your name? (Indonesian: Bisa saya tahun nama Anda?) Adan tiange…. Jerone nyen? My name is…. What’s yours? (Indonesian: Nama saya….. Anda siapa?)

Halus level: Dados uningin parabe? May I know your name? (Indonesian: Bisa saya tahun nama Anda?) Parab tiange….. Sira parab jerone? My name is…. What’s yours? (Indonesian: Nama saya…. Anda siapa?)

Biasa level: Ene poh. Luung sajan. (Indonesian: Ini mangga. Bagus sekali.) This is a mango. It is very good. Ene biu. (Indonesian: Ini pisang) This is a banana.

Halus level: Niki poh. Becik pisan. (Indonesian: Ini mangga. Bagus sekali.) This is a mango. It is very good. Niki pisang. (Indonesian: Ini pisang) This is a banana.

As you can see from the last example, there are often two different words for the same thing, like here the word for ‘banana’ which is biu on the biasa level, but pisang on the halus level of speech. The same thing is true for the expression ‘This is….’, which is ‘niki…..’ on the halus level, but ‘ene…’ on the biasa speech level.

Here are some words typical of Balinese culture:

Odalan temple festival (halus word only)

Pedanda Brahmana priest (pandit in India)

Meru wooden, pagoda-like building with grass roof, named after the holy Mount Meru in India

Naga mythological snake or dragon

Pura puseh temple for the divine ancestors

Pura dalem temple for the dead in the underworld

Another particularity of the Balinese is that people are named according to their order of birth in their family. The names are the same for both males and females, but as an indicator of gender the particle i is used for males and ni for females before the name. Here are the names for members of the farmer caste:

Wayan for the first-born of a family (I Wayan/ Ni Wayan)

Made for the second child

Nyoman for the third child Ketut for the fourth child

A further cultural peculiarity is that the anak Bali will always give directions according to the four directions of the compass instead of using ‘left’ and ‘right’.

North = kaja South = kelod West = kauh East = kangin (all biasa words)

This has interesting implications: While kaja generally means ‘inland, towards the mountains’ ‘in the direction of Gunung Agung‘, the highest and holy mountain of Bali (a prosperous direction), in Southern and Central Bali it therefore means ‘north’ but in Buleleng in Northern Bali it means ‘south’! The same goes for kelod, which means ‘towards the sea’ (a disastrous direction): in Southern and Central Bali it refers to the ‘south’, while in Buleleng in Northern Bali it means ‘north’!

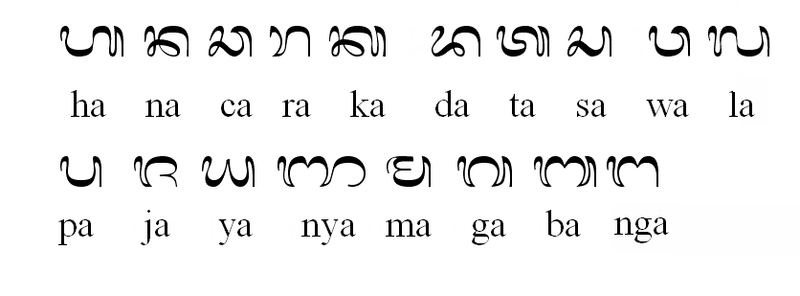

Balinese also has an old indigenous script, the Carakan script:

Bali also has a very rich mythology. According to the Balinese creation myth, in the beginning of time, only the world snake Antaboga existed. During a meditation, Antaboga created Bedawang or Bedawang Nala, a giant turtle who carries the world on her back. Two snakes or dragons (naga) lie on Bedawang’s shell, as well as the Black Stone, which is the lid of the underworld. All other creations sprang from Bedawang. When Bedawang moves, there are earthquakes and volcanic eruptions on earth.

Bedawang = boiling water Nala = fuel

Bidawang means ‘turtle river’ in the Banjar language

The goddess Setesuyara and the god Batara Kala, the creator of light and earth, rule over the underworld. Above the world, there is first a layer of water, then a layer of moving sky, where Semara, the god of love lives. Above this floating sky there is the dark blue sky with the sun and the moon. Yet again above this sky, there is the scented sky full of fragrant flowers, the abode of the human-headed bird Tjak (Cak), of the snake Taksaka and of the Awan-snakes (falling stars). The ancestors live in a fiery sky, located above the scented sky. The abode of the gods forms the final and uppermost layer of the sky.

Etymology: a = not, Ananta = endless, never exhausted, boga = food

Anantaboga = endless food, food that never gets exhausted

A rather good online dictionary for Balinese: http://dictionary.basabali.org/Main_Page

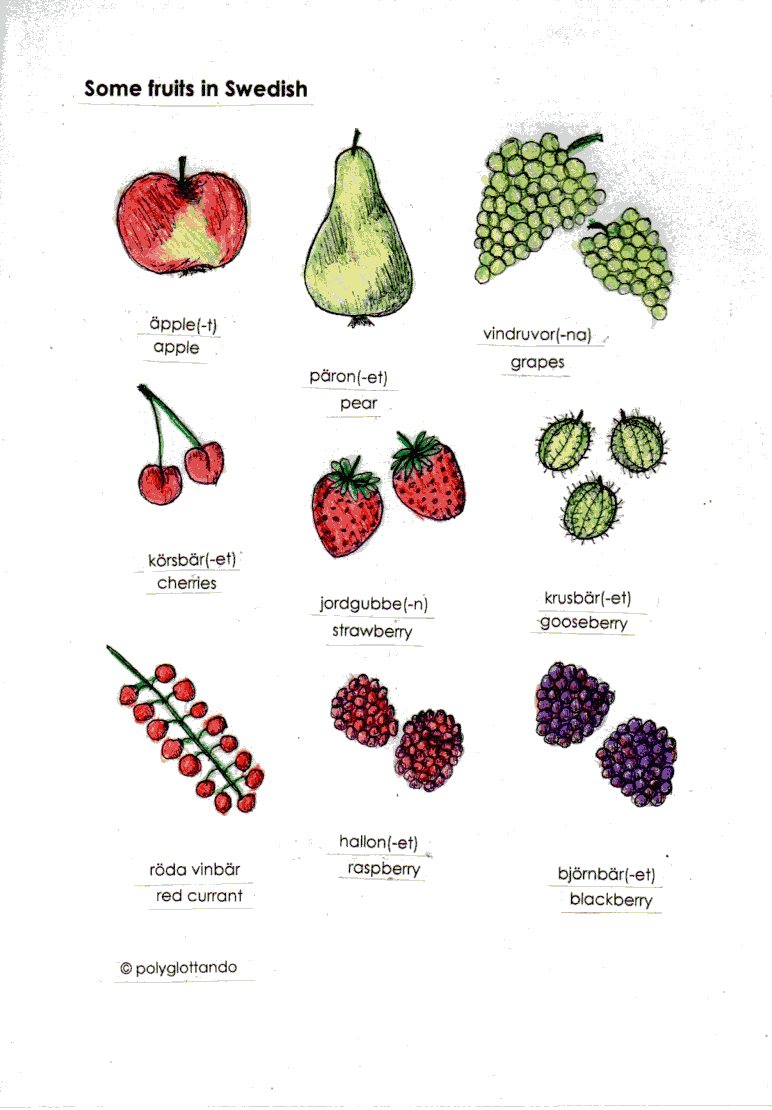

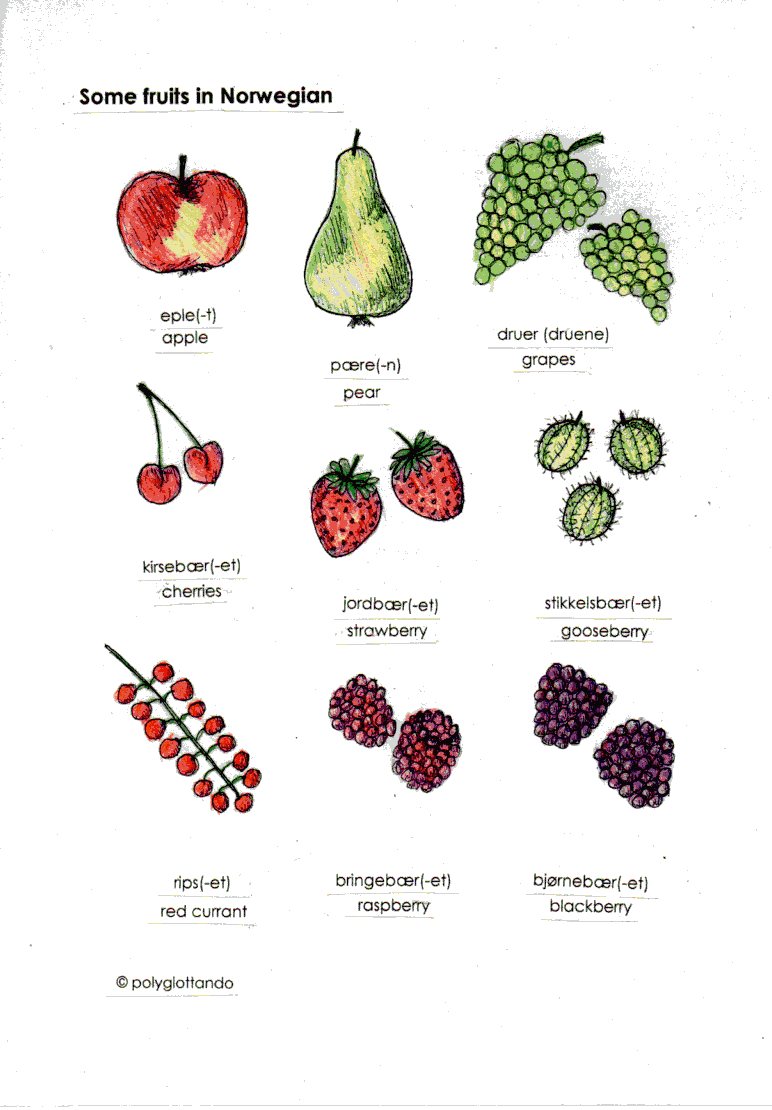

Fruits in Swedish and Norwegian

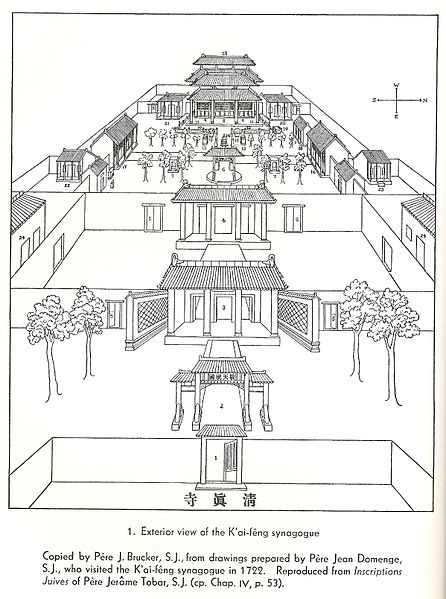

Hebrew: Synagogue vocabulary and architecture

Today’s blog post is taking us to the Jewish world and to synagogue architecture and vocabulary. Synagogues are called בית כנסת beth knesset in Hebrew, which means ‘house of assembly’. Other words for synagogue are בית תפילה beth t’fila, meaning ‘house of prayer’ or שול shul , a Yiddish term used by Jews of Ashkenazi descent, or אסנוגה esnoga, the latter one being a term used by Portuguese Jews. The English or western term ‘synagogue’ is derived from Greek συναγωγή synagogē which means ‘assembly’.

Synagogues have a large hall for prayer, and often also have some smaller rooms for Torah study, called בית מדרש beth midrash or ‘house of study’, and for social meetings and the like. Synagogues are consecrated spaces for prayer; however, communal Jewish worship can take place wherever a מִנְיָן minyan, i.e. 10 Jewish adults, assembles.

The architectural style of synagogues varies widely, and historically, synagogues followed the prevailing style of their location and time. An example is the Kaifeng synagogue, which looked like the Chinese temples of the region.

A central element of all synagogues is the בימה bimah, a table on a raised platform where the Torah scrollתּוֹרָה is read. The reading of the Torah is called קריאת התורה Kriat haTorah.

The Torah is called ספר תורה sefer Torah.

The Torah scrolls are kept in the ארון קודש Aron Kodesh or Torah Ark, a special cabinet which is often closed with an ornate curtain, the פרוכת parochet, which can be inside or outside the doors of the Ark. The Aron Kodesh is the holiest place in the synagogue and is reminiscent of the Ark of the Covenant אָרוֹן הַבְּרִית Aron haBrit which held the tablets with the Ten Commandments. The Ark is usually positioned in such a way that the congregation facing it faces towards Jerusalem. The seating plans of synagogues in the western world therefore usually face east, while synagogues in locations east of Israel face west. Sanctuaries in Israel usually face Jerusalem.

Another traditional feature of synagogues is a continually lit lamp or lantern, the Eternal Light נר תמיד ner tamid which is reminiscent of the western lamp of the מְנוֹרָה menorah of the Temple in Jerusalem, which miraculously remained lit perpetually. Many synagogues also have a large candelabrum with seven branches, reminiscent of the full menorah. Orthodox synagogues feature a מחיצה mechitzah, a partition dividing the seating areas of the men and women, or there is a seating area for the women located on a balcony.